Below is an excerpt from my forthcoming book…

© Mahabodhi Burton

3 minute read

This excerpt commences Chapter 10, ‘Augmentative Conditionality: The Spiral Path.’

The augmentation of conditions

Each Foundation of Mindfulness is a condition for bringing into being a relative degree of happiness or suffering, but due to the Law of Conditionality, the combined effect of all four is augmentative; they are ‘made greater by being added to’; if we look after our body; attend in the right way to feeling; develop increasingly skilful states of mind and emotion; and become clearer about the way that things are and work, then the happiness that we bring to ourselves and others is likely to ‘take off’; this is the meaning of dhyana, which is a result of developing skilful mental states through calming meditation (samatha), and which provide the basis for the development of insight (vipassana), culminating in Awakening; these two stages together constituting what is called the Spiral Path.

The Wheel and the Spiral

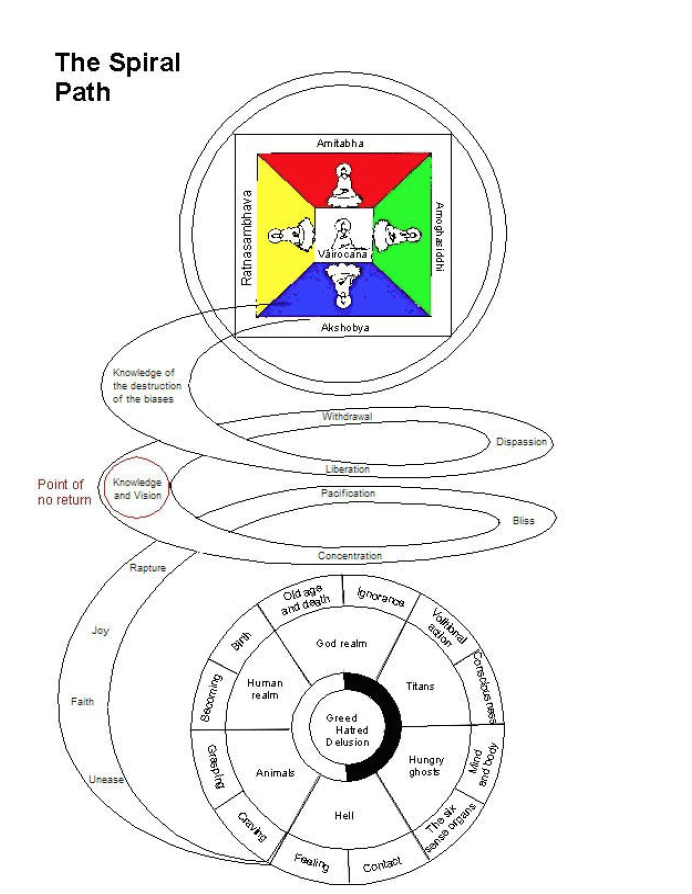

The round of endless suffering and the ascent to Nirvana through augmentative conditionality are represented in the Buddhist tradition by the Wheel of Life[1] and the Spiral Path (see diagram).

Image source unknown. Effort has been made to establish author.

In pictorial versions of the Wheel a ferocious demon called Yama—the ‘Lord of Impermanence’—holds the Wheel like a mirror towards the viewer, as if to say; ‘This is what your life is like.’ At the centre of the Wheel are a pig, a cock and a snake biting each other’s tails, representing respectively ignorance, greed and hatred; the driving forces behind Samsara. Then comes a circle divided vertically into white and black segments, which represents beings rising to greater happiness in the white segment and falling down into greater suffering in the black, according to their karma. Outside of this is a circle, in which there are six ‘realms’, that we can either take literally–as actually existing places—or metaphorically—as psychological states; these are the realms of the gods, titans, humans, animals, hungry ghosts and hell beings. Each is a state one can be born into—or experience—because of one’s karma. On the outer rim are twelve images, each representing a nidana or link: ranging from ignorance through craving all way to old age and death.

The Spiral Path

Sangharakshita has drawn particular attention to the positive nidana sequence leading to Nirvana, which he calls ‘The Spiral Path.’[2] Bhikkhu Bodhi calls this sequence ‘Transcendental Dependent Arising’,[3] lamenting that it doesn’t get the attention it deserves in Theravada Buddhism.[4] The Spiral Path in the Upanisa Sutta is as follows. The first seven links represent the cultivation of samatha or calm.

1) In dependence on unsatisfactoriness (Sanskrit: duhkha; Pali: dukkha), there arises confidence-trust (Sanskrit: shraddha; Pali: saddha)

2) In dependence on confidence-trust, there arises joy (Sanskrit: pramodya; Pali: pamojja)

3) In dependence on joy, there arises rapture (Sanskrit: priti; Pali: piti)

4) In dependence on rapture, there arises calming down (Sanskrit: prashrabdhi; Pali: passadhi)

5) In dependence on calming down, there arises happiness (Pali and Sanskrit: sukha)

6) In dependence on happiness, there arises meditative concentration (Pali and Sanskrit: samadhi)

7) In dependence on meditative concentration, there arises knowledge and vision of things as they really are (Sanskrit: yathabhutajnanadarshana; Pali: yathabhutananadassana)

And the final four represent the cultivation of vipassana or insight;

8) In dependence on knowledge and vision of things as they really are, there arises disentanglement (Sanskrit: nirveda; Pali: nibbida)

9) In dependence on disentanglement, there arises dispassion (Sanskrit: vairagya; Pali: viraga)

10) In dependence on dispassion, there arises liberation (Sanskrit: vimukti; Pali: vimutti)

11) In dependence on liberation, there arises knowledge of the destruction of the biases (Sanskrit: ashravakshayajnana; Pali: asavakkhayanana)

The chapter goes on to explore The Dhyanas.

[1] Buddhist tradition does not isolate the individual conditional relationships (nidanas) between the four foundations of mindfulness as I did in Chapter 9, instead it presents twelve nidanas which it associates with the pull to remain in Samsara (on ‘The Wheel’) and twelve which it associates with progress towards attaining Nirvana (on ‘The Spiral’). These ‘Chains of Dependent Arising’ are outlined in the Upanisa Sutta. The Wheel of Life originated in the Sarvastivadin school and is found all over the Tibetan Buddhist world. See Sangharakshita. (2014) The Three Jewels. Chapter 10, ‘The Wheel of Life.’ Windhorse.

[2] Sangharakshita. (2014) The Three Jewels. Chapter 13 ‘The Stages of the Path.’ Windhorse. Sangharakshita (see A Survey of Buddhism) thinks that Theravada commentators tend to emphasize the destructive aspect of Conditionality; namely that phenomena cease when the conditions that support them cease, overlooking the constructive aspect of Conditionality; those positive qualities—including Enlightenment—are brought into being when the conditions that support them arise. There are many versions of this Spiral Path in the Pali and Chinese Canons. See Jayarava ‘The Spiral Path or Lokuttara Paticcasamuppada’ at

http://www.jayarava.org/texts/the-spiral-path.pdf and Jayarava ‘Dependent Arising: Nidanas’ at

http://jayarava.blogspot.com/search/label/Conditionality

[3] ‘Transcendental Dependent Arising; a translation and exposition of the Upanisa Sutta’ by Bhikkhu Bodhi (1995) Access to Insight.

https://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/bodhi/wheel277.html

[4] As Bhikkhu Bodhi says in his preface to the Upanisa Sutta, ‘Despite the great importance of the Upanisa Sutta, traditional commentators have hardly given the text the special attention it would seem to deserve. Perhaps the reason for this is that, its line of approach being peculiar to itself and a few related texts scattered through the Canon, it has been overshadowed by the many other suttas giving the more usual presentation of doctrine. But whatever the explanation be, the need has remained for a fuller exploration of the sutta’s meaning and implications. We have sought to remedy this deficiency with the following work offering an English translation of the Upanisa Sutta and an exposition of its message. The exposition sets out to explore the second, ‘transcendental’ application of dependent arising, drawing freely from other parts of the Canon and the commentaries to fill out the meaning. Since full accounts of the ‘mundane’ or samsaric side of dependent arising can be readily found elsewhere, we thought it best to limit our exposition to the principle’s less familiar application. A similar project has been undertaken by Bhikshu Sangharakshita in his book The Three Jewels (London, 1967). However, since this work draws largely from Mahayanist sources to explain the stages in the series, the need has remained for a treatment which elucidates the series entirely from the standpoint of the Theravada tradition, within which the sutta is originally found.’—Commentary within Bhikkhu Bodhi. (1995) ‘Transcendental Dependent Arising; a translation and exposition of the Upanisa Sutta.’

Users Today : 8

Users Today : 8 Users Yesterday : 42

Users Yesterday : 42 This Month : 76

This Month : 76 Total Users : 14237

Total Users : 14237