Below is an excerpt from my forthcoming book…

© Mahabodhi Burton

8 minute read

This excerpt is from the chapter ‘Safetyism,’ and explores its remedy in the fearless qualities of the dark green Buddha Amoghasiddhi (‘Unobstructed Success.’)

Fearlessness

So, what is the remedy for Safetyism? Obviously, fearlessness: a quality that the Buddha was known for. Vessantara:

‘On another occasion the Buddha’s cousin, Devadatta, in a fit of jealousy, bribed someone to let loose a wild elephant against the Buddha. We can imagine the scene: people scattering in all directions; Devadatta perhaps hidden somewhere out of harm’s way where he could watch events; the great beast rushing, maddened, towards the one still figure in a mud-dyed yellow robe. It is an extraordinary contrast. The elephant out of control, head tossing, trunk waving, furious; the Buddha still, erect, serene. … As the beast came towards him, the Buddha suffused it with maitri, loving-kindness. Nothing could have entered that enchanted circle of love around the Buddha and maintained thoughts of violence. The mad elephant discovered it was bearing down on the best friend it had in the world. Gradually its charge slowed to a walk, and it reached the Buddha docile and friendly. In this incident we could say that elephant met elephant, for the Buddha was often described as being like a great elephant because of his calm dignity and steady gaze. Perhaps elephant met elephant in a deeper sense too. The Buddha, having gone far beyond dualistic modes of thought, did not feel himself a separate, threatened identity opposed by the huge creature bearing down upon him. His maitri (love) came from a total feeling for, and identification with, the charging animal.’[1]

Fear is not overcome by bravado:

‘… ultimately (fearlessness) can come only from insight into Reality. At that point we realize the illusoriness of the ego which we feel for. In particular, fear of dying, the primary fear of which all other are reflections, disappears. … The double vajra reminds us that fearlessness comes from a full and balanced development of all sides of ourselves. Without that, we shall always have a weak side, a vulnerability that we fear for, and keep having to protect. Even more, we shall have an unexplored aspect, an area of uncharted terrain within, whose characteristics we may experience, projected onto the outside world, as people and situations that are unpredictable and threatening. … It is all too easy to keep developing one’s strengths, and to try to make use of them in all situations. Some people even manage to become totally identified with a single talent or a powerful position. From the spiritual point of view this is dangerous. If you wanted to defend the castle, you would not work to make just one or two sides impregnable.’[2]

Ethical Robustness

‘Putting on the heavy armour’

To overcome fear we may need to develop the Spiritual Faculty of viriya,[3] which is sometimes translated as diligence or ‘energy in pursuit of the good.’[4] As I said in Chapter 1, I call viriya ‘ethical robustness,’ because it implies holding to a skilful ethical outlook under all conditions (specifically under the temptations of seeking pleasure and avoiding pain.) It is therefore described as a powerful inclination towards the skilful; a brave mode of action; diligence which is ever-ready, which Yeshe Gyaltsen characterizes as ‘putting on the heavy armour.’[5] Viriya has four further aspects.

Diligence which is applied work

Sometimes life is a joyless slog; at other times we are carried along on a wave of enthusiasm. The first mode will eventually lead to the second.

‘Directing one’s energies towards what one knows to be wholesome in a steady, systematic, persistent way—albiet without a lot of joy—will have positive effects, and enthusiasm will naturally tend to arise more and more as one keeps going.’[6]

Sometimes the opposite is the case.

‘One’s enthusiasm can sometimes melt away and then viriya consists in carrying on without it. … Enthusiasm is not necessary in order to keep up a steady practise. Motivation, enthusiasm, and inspiration will arise as long as we just get on with the job.’ [7]

Diligence which does not lose heart

This is viriya as stout heartedness, applying oneself with courage and confidence, not losing heart in moments of personal frailty. It calls for a measure of shraddha in the sense of confidence in one’s own potential.[8]

Diligence which does not turn back

It is almost always the case that we run into obstacles we had not anticipated; but we don’t abandon our original intention, just because the going has become more difficult than we expected.

Diligence which he’s never satisfied

One never rests on one’s laurels: the very nature of viriya is that it goes on and on, as long as there is something higher to be achieved—and of course there always is.

In Chapter 12 I will go on to explore how—when we have a rounded and full development of the five spiritual faculties, there will be no aspects of our personality that will come to be a cause for suffering for ourselves or others. However, when one Spiritual Faculty is undeveloped—as when we lack Ethical Robustness—suffering ensues.

We met the dark green Buddha Amoghasiddhi on page 13. He is ‘head’ of the action or karma family, and his name means ‘Infallible or Unobstructed Success:’ his wisdom All-Accomplishing Wisdom. He represents success in the world, that achieved by Enlightened Consciousness. He brings the qualities of Enlightenment into the world without them being sullied. Personalities who come to mind here are Mikhail Gorbachev and Abraham Lincoln: what an astonishing feat to peacefully transition the Soviet Union from a communist to a social democratic state; or to use his wile to make sure that slavery in the US ended peacefully. We might then associate Amoghasiddhi with diplomacy.

Image copyright Amrta.

Amoghasiddhi’s right hand is held vertically in front of his chest: palm facing outwards, in a gesture of fearlessness, called the abhaya mudra.

‘The path of Amoghasiddhi, then, is a path of overcoming fear.…[It] involves courageously diving into the midnight depths of ourselves, finding there the blueprint of our potential, and being prepared to work on the weakest and most embryonic aspects of ourselves… This is no easy path to follow, but if we take up the challenge then all the time that we are working to overcome our fears the calm, dark green figure of a Buddha will stand by our side … bestowing on us the courage and confidence to follow that path to the end.’[9]

The polarization that we see increasingly today is based in fear; fear of our needs not being met; fear of that which appears different; however, Amoghasiddhi represents the union of opposites: he suggests reconciliation with the other side; listening to the other side. He suggests coming out of our information silo and engaging with the reality of the full picture, which will eventually come to us even if we don’t go to it.

His fearlessness grows out of a deep sense of integration, which is equally at home in the quiet of meditation practice and the hurly-burly of acting in the world: today, he is the one who is equally at home with Left and Right: a rare occurrence. In his left hand, placed in his lap, he holds a double-vajra:[10]

‘In the depths of the midnight sky then appears a giant double-vajra. The two diamond thunderbolts are crossed and made of pure crystal. As we saw when we met Aksobhya, the single vajra is a symbol of awesome power and force. It can cut through anything whilst always remaining unaffected. Nothing mundane can withstand its impact. The double vajra has all these qualities reinforced. … [It] is a symbol of total psychic integration, of the unfoldment of all potential, of perfect harmony, balance, and equilibrium. It can only be encountered when one has journeyed into the most profound depths of existence. It can only appear out of the midnight sky of the deepest unconscious.’[11]

Overcoming anxiety

Each Buddha has an associated animal, which represents an aspect of his energy. Amoghasiddhi flies through the sky—like the Greek god Mercury—supported by two garudas or birdmen, clashing cymbals together; We might think that this is not a particularly peaceful Buddhist image, but it makes me think of a therapy used to combat anxiety: Exposure Therapy.

What a person does in that therapy is they list all the things they are most afraid of: with the most fearful at the top. They then try to consciously face the least fearful in the list. Once they have become accustomed to that and no longer afraid of it, they then tackle the next in the list. Thus, they gradually expose themselves to their fears, as represented by the clashing symbols, until they are no longer afraid of them: we might call this strategy ‘graded exposure.’

Each Buddha is associated with a skandha: a constituent of the human personality:[12] the one associated with Amoghasiddhi is volition or samskara. And the mental poison associated with Amoghasiddhi is envy, which obviously comes up for others whenever we are successful, and therefore we must deal with it.

Amoghasiddhi and the hierarchy of religion

I suggest we consider Amoghasiddhi to be the (Buddhist) ‘patron saint’ of religion: he is associated with action; ritual is symbolic action; and religion is associated with ritual. When we deal with religion, we often must deal with fear: it is part of the package, and why fearlessness is so important.

Firstly, fear often comes up when we face the unknown, and the concern of religion is to deal with the unknown.

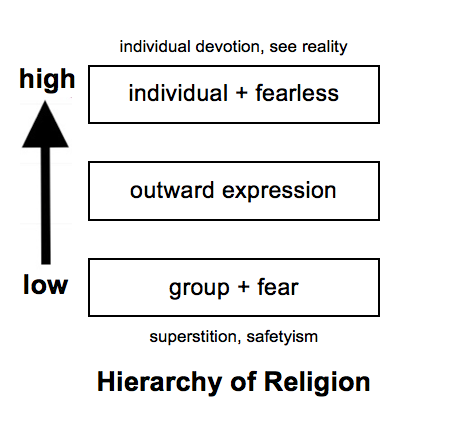

Secondly, fear comes up when we give outward expression to our beliefs: in a way, religion is simply the outer expression of our first-person values. Amoghasiddhi oversees our bringing those values into the world successfully; remember the hierarchy of religion.

Sometimes we can stand with integrity in our religion, in facing the hostile opinions of others who hold rival beliefs; but at other times we may need to feel the support of the group to bolster our confidence. So, we have a spectrum within religion: at the ‘high end’ we have the fearless individual expressing genuine devotion to high Ideals, for instance, an individual practising a Universal Religion with individual faith and commitment: maybe a Buddhist on a long retreat in a cave practising heartfelt devotion or puja.

The ‘low end’ of the spectrum we have more of a group-based religion. Here religious practice is marked by superstition and fear—for instance, an Ethnic Religion such as Hinduism, in which villagers, faced with the challenges of life, in fear employ the Brahminical priest to propitiate the Gods with animal sacrifice.

Such religion is essentially superstitious. An example of superstition is when we cross our fingers and hope for the best: an action which acknowledges some sort of ethical or hierarchical structure to the Universe, but which is vague about what that structure is. The superstitious person experiences the impulse to ‘do something’ in the face of the fearful unknown; and having done that something, they feel better.

Safetyism, then, is a similarly superstitious response to life’s difficulties. But what is the solution? The solution involves ‘looking up’—as in the film Don’t Look Up;[13] it involves coming out of our information silo into the light; it involves facing reality as it is; it involves choosing higher values over lower; and it involves maintaining those values in the face of opposition; this is what the dark green Amoghasiddhi potentially gives to us.

The chapter ends here.

[1] Vessantara. (1993) Meeting the Buddhas. Motilal Banarsidass: Delhi. p110.

[2] Ibid. p111.

[3] See Sangharakshita. (1998) Know Your Mind: the Psychological Dimension of Ethics in Buddhism. Windhorse. p141-4.

[4] A skilful (kusala) mental state is one that—by its very nature—leads to happiness and an unskilful (akusala) state is one that leads to suffering. Viriya consists in putting our energy into the cultivation of the four right efforts, namely: 1) Preventing unskilful mental states that have not yet arisen; 2) Eradicating unskilful mental states that have arisen; 3) Cultivating skilful mental states that have not yet arisen; 4) Maintaining skilful mental states that have arisen.

[5] Yeshe Gyaltsen. (1975) Mind in Buddhist Psychology: Necklace of Clear Understanding by Yeshe Gyaltsen. Dharma Publishing. p48-52.

[6] Know Your Mind p142-3.

[7] Ibid p143.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid. p111.

[10] In Buddhist cosmology the Universe itself rests on a giant double-vajra. As the vajra itself is a Tibetan symbol for reality; the double-vajra points to an even more fundamental level of that reality.

[11] Ibid. p107.

[12] ‘Skandha. In Sanskrit, lit. “heap,” viz., “aggregate,” or “aggregate of being”; one of the most common categories in Buddhist literature for enumerating the constituents of the person. According to one account, the Buddha used a grain of rice to represent each of the many constituents, resulting in five piles or heaps. The five skandhas are materiality or form (rupa), sensations or feeling (vedana), perception or discrimination (samjna), conditioning factors (samskara), and consciousness (vijnana). Of these five, only rupa is material; the remaining four involve mentality and are collectively called “name” (nama), thus the compound “name-and-form” or “mentality-and-materiality” (namarupa). However, classified, nowhere among the aggregates is there to be found a self (atman). Yet, through ignorance (avidya or moha), the mind habitually identifies one or another in this collection of the five aggregates with a self. This is the principal wrong view (drsti), called satkayadrsti, that gives rise to suffering and continued existence in the cycle of rebirth (samsara).’ Buswell Jr., Robert E.; Donald S., Jr. Lopez. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

[13] Don’t Look Up. (2021) IMDb.

Users Today : 58

Users Today : 58 Users Yesterday : 23

Users Yesterday : 23 This Month : 516

This Month : 516 Total Users : 13943

Total Users : 13943