Below is an excerpt from my forthcoming book…

© Mahabodhi Burton

10 minute read

This excerpt is from the chapter ‘The Evidence Bases in Religion, Science and Politics,’ in which I explore how kindness is developed through paying attention to what living beings truly are: a process Tse-Fu Kuan calls ‘Constructive Imagination.’

Feeling and emotion

Metta—Universal Loving Kindness–is one way that we redirect our emotions along the most wholesome pathway; it is, however, very important first to be clear about the difference between feeling (vedana) and emotion–as an aspect of ‘mind’ or citta. Sangharakshita:

‘When Buddhist psychology refers to developing mindfulness of feelings, however, something rather different is meant from the “getting in touch with one’s feelings” with which psychotherapy is concerned–something less complex, perhaps more useful. Indeed, being able to identify feelings (in the sense of vedana as defined by the Buddhist tradition) is what makes it possible for us to follow the Buddhist path. The Pali term vedana refers to feeling not in the sense of the emotions, but in terms of sensation. Vedana is whatever pleasantness or unpleasantness we might experience in our contact with any physical or mental stimulus.

‘To understand what we would call emotion, Buddhism looks at the way in which that pleasant or painful feeling is interwoven with our reactions and responses to it.’[1]

Feeling as vedana, then, is just experience: specifically the experience of pleasure, pain or neither. On the other hand, the etymology[2] of the word ‘emotion’ is connected with ‘moving out,’ in the sense of ‘responding.’ Emotion, then, is that aspect of the mind or psyche (Pali: citta) which ‘moves in relation to experience.’ Citta encompasses the sum total of how the psyche moves in response to experience: it therefore includes thinking, emotion and the distribution of attention:

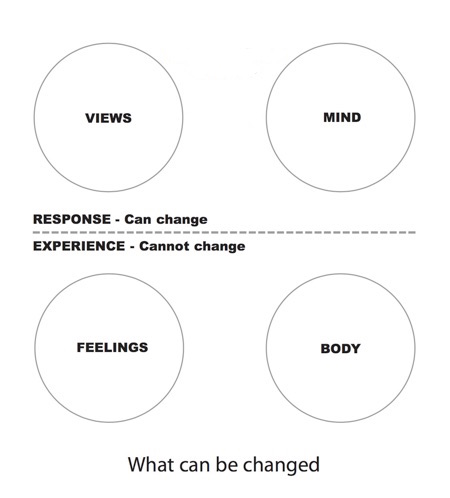

It is useful to consider the above diagram. In the teaching of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness (satipatthanas,) the Buddha says we need to bring mindfulness to four areas, if we are to bring happiness into the world, avoid suffering and ultimately attain Nirvana.[3] These foundations are body (kaya,) feeling (vedana,) mind (citta) and views (dhammas) and they all condition each other. Usually that conditioning, when taken between feeling and emotion, involves moving towards pleasurable experiences that are desired and away from painful experiences that are undesired—and maybe not responding at all to neutral experiences. Emotion then is most of the time an unconscious and reactive response to feeling; while feeling and the emotion feel to be one thing, they are actually distinct. Feeling is just what is presented to us in the moment: thus, it is something we cannot change: however, emotion, as a response can be changed.

Emotion and samskaras

The Buddhist word samskara (Sanskrit; Pali: sankhara) can be understood as the habitual tendency to want certain things. In its etymology, it is connected with ideas such as construction and fabrication; and also with the will.[4] When we talk about a person’s samskaras we usually mean their disposition to act in particular ways—such as their tendency to get angry or to act as a victim: important for the practitioner to know because they strongly condition their current mental states: thus on the outer rim of the Tibetan Wheel of Life, samskaras come second after ignorance and belong in the causal process of the past life:[5] based upon ignorance (a blind man with a stick,) certain karmic tendencies come into being (signified by a potter at his / her wheel:) that is a ‘world’ is made, which—being itself situated on the Wheel–is necessarily subject to old age, sickness and death.[6]

But samskaras are also associated with the present moment mental states (caittas)[7] and therefore with the psyche’s mental and emotional response.[8]

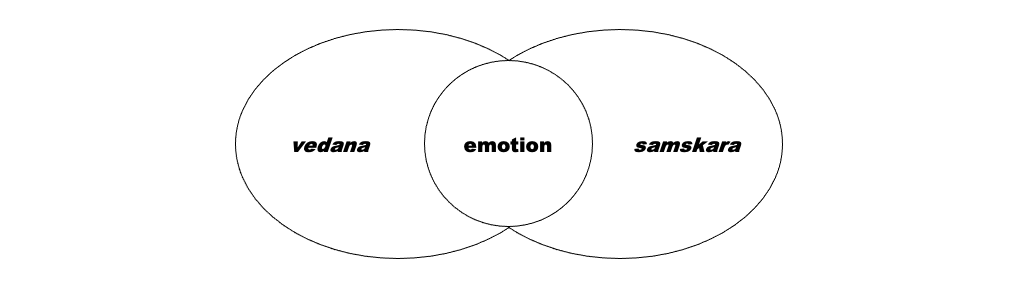

Both Sangharakshita and Tse-fu Kuan make attempts to relate vedana, emotion and samskaras. Sangharakshita:

‘In Buddhist psychology, vedana is said to combine with samskara, a volitional quality involving a tendency towards action. It is this combination of sensation with volition that approaches what we would recognize as fully developed emotion.’[9]

Tse-fu Kuan holds a similar view:

‘Emotion can be the transition from the original feeling to [samskara.]’[10]

which he illustrates with a diagram:[11]

I would put things slightly differently: samskaras—in the sense of ‘emotional responses’—arise not only in dependence upon feeling (vedana,) but also in dependence upon other conditions: one of which is apperception / recognition (Sanskrit: samjna; Pali: sanna.) Sanna is a Buddhist technical term sometimes translated as ‘perception,’ but more accurately it is ‘apperception,’ meaning something like recognition (once we know the name ‘chair,’ then we have the possibility of recognizing—or apperceiving—a chair when we see one.)

Tse-fu Kuan proposes emotions to be:

‘Secondary feelings conditioned by sanna [apperception]…’[12]

If we understand apperception to be a key factor in conditioning our Views, then what we have is a picture which conforms to experience: not only are emotions conditioned by feelings but they are conditioned by views. This gives us a fuller picture of the operating conditions behind emotion:

Universal Loving Kindness (metta)

The Buddhist term for kindness is metta, or in Pali maitri. It is not usually translated by a single English word like ‘love’ because that term often brings with it unhelpful connotations of romance and attachment. Metta is really the care we feel for a person we live in the straightforward way of wanting a person to do well and be well: the kind of emotion we might feel for a family member or a good friend. However, it extends further than that: sometimes people have talked about metta as unconditional positive regard.

To deliver a fuller picture of what metta truly is, we need to reflect on its three inherent qualities—metta is universal; unconditional; and illimitable.

Metta is illimitable

The first thing to note is that metta is an emotion (and not a feeling;) it may condition one of more feelings but it is really important to be as clear as we can that metta is an emotion: as such it is a response to experience, not an experience in itself. It is a response to the plight of one of more living beings, and crucially that includes a caring response towards oneself.

When I talk about a response there can be an idea in some people’s minds of making effort; of trying; of willing something into existence. The metta bhavana meditation is ‘the cultivation of universal loving kindness’ and as such is a developmental practice within Buddhism, but this doesn’t necessarily mean forcing something to happen. I think Westerners are so habituated to having to over-ride their feelings when they do not want to do something that they apply the same principle to the metta bhavana when they come to learn it.

The point is not to sincerely strain but to be effective in our cultivation, which means being intelligent, not wilful. Just as a gardener cannot force his plants to grow but instead pays keen attention to the conditions needed for growth, so too the meditator does whatever is necessary for metta to develop.

Metta is an emotion, and if we think about it, emotions are often about wanting. Think of a few: greed, desire, lust, envy, to name a few, are all about wanting something: sensory experiences, sexual gratification, a thing that someone else has. Or they are about not wanting something, as with hatred (wanting a person to suffer,) aversion (not wanting certain experiences,) disgust, and so on. Or a person is indifferent in what they want. There is nothing wrong with wanting per se—it is just a question of wanting the right things: that which leads to the welfare of living beings.

The word ‘want’ can have a connotation of lack, as in the phrase: ‘his commitment was found wanting.’ Maybe this is why some Buddhists are suspicious of using the word in speaking of metta: it smacks of neediness. But so long as we distinguish between a neurotic wanting based in lack and a wholesome wanting based in a spirit of awareness and generosity I don’t think there is a problem. In fact, ‘wanting’ conveys an appropriate level of passion, when applied to metta.

Emotions vary in intensity: we might be mildly interested in getting a new car, or we might be completely obsessed with getting one: it is exactly the same with metta. We might want ourself or another to be happy in a lukewarm sort of way or we might be completely passionate about them achieving it: this is why metta is called an ‘illimitable:’ there is no limit to the intensity with which we might feel it; I always think of the Dalai Lama in this regard: how passionately interested he is in each and every person who comes in front of him.

Metta is unconditional

Secondly, metta is unconditional: it isn’t something that we cultivate in order to get something back—the fact that living beings desire happiness is reason enough for us to want it for them.

Sometimes compassion for the welfare of others becomes all about us; when we are constantly thinking in terms of our compassion; our spiritual progress; in this case, there is a problem.

Metta as universal

The Buddha taught in the Karaniya Metta Sutta that we should bring forth an all-embracing love for all the world—just as a mother would protect with her life her only child:

‘Just as a mother would protect her own son, her only son, with her life, so one should develop the immeasurable mind towards all beings and loving kindness towards the whole world. One should develop the immeasurable mind, upwards, downwards and across, without obstruction, without hatred and hostility. Standing, walking, sitting, or lying down, as long as one is free from drowsiness, one should practise this mindfulness. They say, “This is a divine dwelling in this world”.’[13]

Such an attitude arises when we consider:

The needs of living beings

For food, water, warmth, shelter, health, intimacy, self-expression and meaning in their lives: and how they experience happiness when these are satisfied (Maslow’s hierarchy of needs)

That actions have consequences

That every action that we perform or omit to perform, whether of body, speech or mind, will have a beneficial, neutral or detrimental effect on the living beings around us

That we are potentially interconnected every living being in the universe

That to a greater or lesser extent this in the case: thus, we need to try to make our influence on each living being as beneficial as we can

Metta as ‘Constructive Imagination’

In Mindfulness in Early Buddhism Tse-fu Kuan argues that the cultivation of metta comes down to constructive imagination.

‘To cultivate loving-kindness towards all sentient beings and conceive of them as being one’s own son involves “constructive imagination.” This is a process of morally constructive transformation of one’s sanna [What one recognizes about a thing] by means of deliberate conceptualizing.[14]

He is referring to the Tibetan Buddhist practice of viewing sentient beings as a mother would her son. Notice he says ‘morally constructive transformation,’ meaning, I construe, that we recognize what is present through a moral lens: our response to any living being depends on how we view them, so we need to view them accurately. In other words, constructive imagination involves transforming what we recognize about a living being to seeing them as a living being, sensitive to their experience.

Seeing people as objects

Often, we don’t perceive ourselves—or others—as living beings in the full sense of the term. Instead, we think of them narrowly in terms of their occupation, role, or usefulness: our approach is instrumental. We view living beings as ‘objects’, rather than what they truly are: living beings sensitive to their experience.

Our view of each living being is often moulded by what we want or don’t want from them: they thus appear as object of desire; objects of pleasure; objects of usefulness; as simply objects; or as objects to be avoided or objects in our way! And, to the extent that we treat a being as a sexual object or a ‘cash-cow’, we cease to treat them as a human being: and this will be a source of suffering to them. The above thoughts follow Sangharakshita in his teaching of metta as being ‘the awareness of the being of another person.’

Tse-fu Kuan expresses a similar connection between mindfulness (sati) and metta in Mindfulness in Early Buddhism:

‘Loving-kindness is among the four immeasurable states (appamanna) or divine dwellings (brahmavihara): loving-kindness (metta), compassion (karuna), altruistic joy (mudita) and equanimity (upekkha). Just like upekkha, … loving-kindness may also be counted as a type of emotion produced by deliberately transforming sanna, which is the job of sati. While the Metta Sutta mentions “this mindfulness” (etam satim), it probably does not mean that loving-kindness itself is a kind of sati, but it implies that the process of developing loving-kindness involves sati.’[15]

Seeing beings for what they truly are: living beings

Caring for somebody isn’t automatic—which is why metta needs to be cultivated when it is not present. One of the ways we do that is we try to transform our sanna until it is in line with reality. If we see a living being as an object, there is no reason why we should care for them; but if we bring mindfulness to each being and recognize them clearly as an individual: with feelings, hopes and desires, who cares about their experience—then we will naturally care for that being; in this way, seeing people for what they are is an aspect of what the Buddha called Right View.

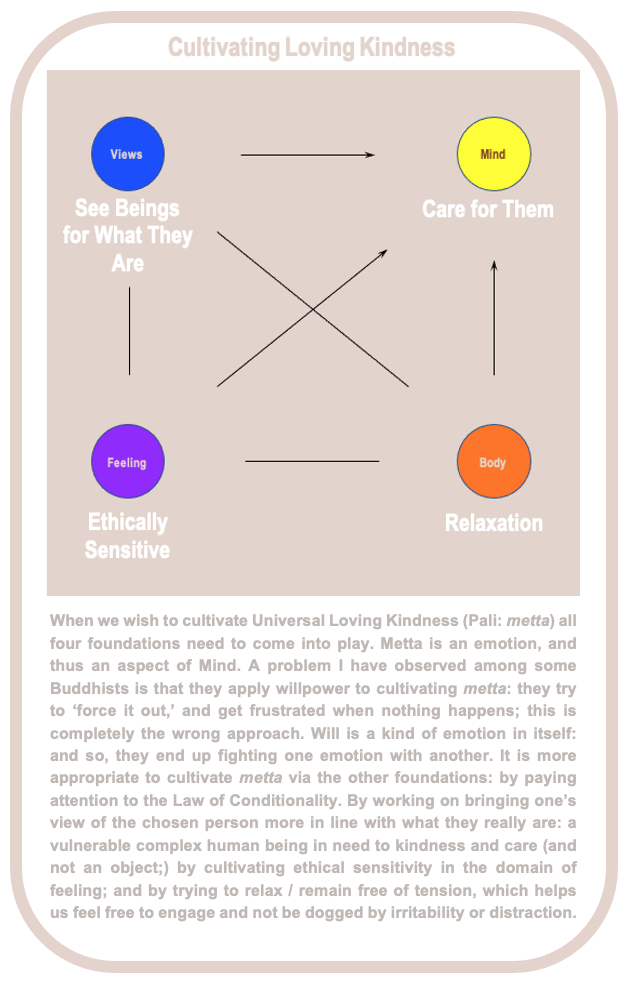

In the teaching of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness (satipatthanas,) the Buddha says we need to bring mindfulness to four areas, if we are to bring happiness into the world, avoid suffering and ultimately attain Nirvana. These foundations are body (kaya,) feeling (vedana,) mind (citta) and views (dhammas) and as we can see in the diagram below, they condition each other. Citta encompasses the sum total of how the psyche moves in response to experience: it therefore includes thinking, emotion and the distribution of attention. Improving our view of living beings to make it more accurate therefore leads us to care for them (see diagram:)

Of course, such clarity—about ourselves and others as living beings—will ‘drift in and out of focus:’ some days we will be clear what living beings are and care for them accordingly: on others we plunge back into habitually seeing ourselves and others as objects and thus be unrelentingly critical of ourselves about failing to complete the tasks on our to-do list in the allotted time. This is why it is important to practise the metta bhavana every day: to keep up this sense of care; we will explore how we practise the metta bhavana in Chapter 9.

At its most elevated, then, metta is the infinitely intense, unconditional love for all sentient beings—and it depends on constructive imagination.

The chapter continues by exploring how kindness manifests in different religions.

[1] The Essential Sangharakshita: a half-century of writings from the founder of the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order. p393-4.

[2] Emotion: Latin emovere, from e– ‘out’ + movere ‘move.’

[3] For a fuller explication see Chapter 8.

[4] Samskara as a Buddhist term which means ‘that which has been put together’ or ‘that which puts together’—and it is variously translated as ‘formation’, ‘fabrication’, ‘volitional formation’, ‘volitional activity.’

[5] See Kennedy, Alex (Dharmachari Subhuti.) (1985) The Buddhist Vision: an introduction to the Theory and Practice of Buddhism. Windhorse. p110-1.

[6] Ibid. p89-94.

[7] Such as the 51 mental events identified in the mature Yogachara system of the Mahayana Abhidharma. See Buswell Jr., Robert E., Donald S., Jr. Lopez. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (pp. 495-496). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

[8] ‘Samskara is also the name for the fourth of the five aggregates (skandha), where it includes a miscellany of phenomena that are both formed and in the process of formation, i.e., the large collection of factors that cannot be conveniently classified with the other four aggregates of materiality (rupa), sensation (vedana), perception (samjna), and consciousness (vijnana). This fourth aggregate includes both those conditioning factors associated with mind (cittasamprayuktasamskara,) such as the mental concomitants (caitta), as well as those conditioning forces dissociated from thought (cittaviprayuktasamskara), such as time, duration, the life faculty, and the equipoise of cessation (nirodhasamapatti.)’ Buswell Jr., Robert E.; Donald S., Jr. Lopez. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (p. 2189). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

[9] The Essential Sangharakshita: a half-century of writings from the founder of the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order. p394.

[10] Tse-fu Kuan. (2008) Mindfulness in Early Buddhism: new approaches through psychology and textual analysis of Pali, Chinese and Sanskrit sources. Routledge. p27.

[11] Ibid. p28.

[12] Ibid. p24ff.

[13] DN III 139-140. See Mindfulness in Early Buddhism. p55.

[14] Ibid. p55-6.

[15] Mindfulness in Early Buddhism. p55-6. For ‘constructive imagination as deliberate conceptualizing’ see Hamilton, Sue. (1996) Identity and Experience: The Constitution of the Human Being According to Early Buddhism. London: Luzac Oriental. p61.

Users Today : 2

Users Today : 2 Users Yesterday : 25

Users Yesterday : 25 This Month : 208

This Month : 208 Total Users : 17061

Total Users : 17061

February 11, 2024

Beautiful clear expression , of some hugely important points which need to inform the Metta-bhavana teaching. I was particularly struck by the inappropriateness of WILL in the development of metta.. This was made so clear and succinct.