Below is an excerpt from my forthcoming book…

© Mahabodhi Burton

14 minute read

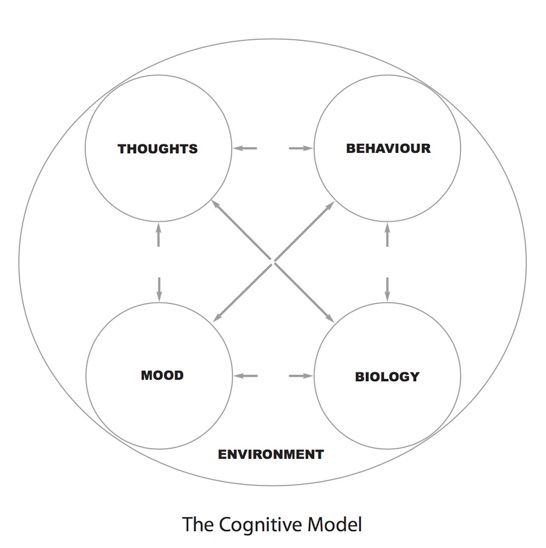

This excerpt is from the chapter ‘The Undiscovered Foundations’ and it explores the way in which the Buddha’s teaching on Conditionality; that all phenomena arise in dependence on (multiple) conditions applies in the case of the Buddha’s central teaching on mindfulness: namely the Four Foundations of Mindfulness. In this case we see how the body conditions the other Foundations: namely feeling, mind (including emotions) and views, in a manner similar to the cognitive model from Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. This excerpt follows on directly from The Satipatthana Sutta.

ii The Cognitive Model

Although the principle of Conditionality is explicit in Buddhism, we can see it operating implicitly in other fields, such as in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). CBT is a psychotherapeutic intervention which looks at what can be observed and worked with on the ‘surface’ of our experience, rather than focusing on our internal states. It’s cognitive model[1] identifies four factors that influence moods, such as from depression or anxiety, and which, when changed, will change the mood.

- Environment–a mood can be changed by altering ones’ ‘psychosocial’ (physical or social) environment. To improve one’s mood one might choose to socialize with people who are positive and cheerful, or to tidy one’s flat.

- Biology / ‘Physical reactions’–a mood can be changed by altering ones’ bodily state, by taking better care of it, exercising more, getting better sleep, eating more nutritious food, and so on. When a depressed person takes exercise, thus generating greater vitality in their body, it is natural that their mood will lift to some extent.

- Thoughts–a mood can be changed by altering one’s thoughts, by consciously cultivating more balanced (less catastrophic) thoughts; one puts one’s thoughts ‘on trial.’

- Behaviours–a mood can changed by looking for the effect of one’s behaviour on one’s mood and acting accordingly; if acting in a more friendly manner, even when one does not feel like it, improves ones’ mood then one should do that.

iii Conditionality at work between the Four Foundations of Mindfulness

Correlation between the Four Foundations of Mindfulness and the Cognitive Model

Although the foundations are presented in a linear fashion, one after the other, in the Satipatthana Sutta they don’t stand from in isolation and the real juice occurs in the interplay between the foundations. If we are to understand how mindfulness works, we cannot treat the foundations in isolation, but need to see clearly how they are affected by each other. Perhaps as they both concern the human being and its’ situation it is not surprising that the four foundations and the four central aspects of the cognitive model exhibit certain correlations, and that the four foundations can be arranged in a similar structure to the Cognitive Model.

| Foundation of Mindfulness | Cognitive Model |

| Body | Biology |

| Feeling | Mood |

| Mind | Behaviour |

| Views | Thoughts |

Clear Comprehension

This arrangement helps us understand everything from that is important in the human quest for happiness, well-being or fulfilment. Where mindfulness (sati) is the action of bringing awareness to an object, it cannot be separated from clear comprehension (sampajanna), which is the mental quality which holds a clear overview.[2] That overview has four aspects;[3] when one possesses them, one understands exactly;

- What one is doing: We know, and keep drawing our mind back to, the overall direction we are taking in the Buddhist soteriological project, i.e., mindfulness of purpose (satthaka sampajanna)

- What ‘domain’ one is dealing with: We are clear what exactly is meant by the terms body, feelings, mind and views, and when they are present in ones’ awareness, i.e., mindfulness of domain (gochara sampajanna)

- What factors condition that domain: We know precisely how each Foundation is conditioned, and how the relevant conditioning factors need suitable attention if we are to overcome suffering, i.e., mindfulness of suitability (sappaya sampajanna)

- The overarching Enlightened perspective on reality: We possess that perspective when we understand completely how suffering is overcome, i.e., complete non-delusion (asamoha sampajanna)[4]

One of the main reasons why I wanted to write this book was to clarify the way in which mindfulness might lead to Nirvana. In this next section I develop a clear comprehension of the mechanisms that are in play when we bring together the four foundations of mindfulness and the doctrine of Conditionality. Not everyone is always interested in technicalities of the ‘how’, and if this is the case with you, you might want to skip this section and move on to the next chapter.

Experience and response

The first evaluation we need to make, if we are to bring happiness to ourselves and others through mindfulness practice, is we need to distinguish between the domains we have control over and those we don’t.

The foundations of body and feeling as EXPERIENCE

In any given moment we have a particular experience of the body and the objects of the senses; we also have a particular experience of pleasure, pain or neutral feeling in each moment. In the moment that we experience them, these experiences are ‘a given;’ as such they are something we can do nothing about. In this way I am viewing the foundations of body and feeling as EXPERIENCE, over which we have no control.

If the monk is tense, he is tense. In pain, in pain. Happy, happy; the monk is always experiencing something. He might want to work to change that experience, but in the moment that he is presented with it, that is his experience.

The foundations of mind and views as RESPONSE

However, the monk is not merely the passive recipient of experience; he has control over his RESPONSE to his experience, which I am here identifying with the foundations of mind and views (he chooses his mental states and his views), where mind is the way that his whole psyche actively responds to his experience, and views the assessment of his situation that he adopts in the moment; his ‘map of the world, which like his mental states, can be changed.

iv Primary conditional relations

If we accept the view that the four foundations of mindfulness condition each other, as there are three ways in which each foundation can condition another, this gives us twelve ‘primary processes’ that operate between the foundations and have a bearing on happiness / well-being / Awakening;

We can approach them in the order that the Buddha teaches the four foundations in the Satipatthana Sutta, namely;

- Mindfulness of the body / tangible objects conditioning Awakening

- Mindfulness of feeling conditioning Awakening

- Mindfulness of mind conditioning Awakening

- Mindfulness of views conditioning Awakening

v Mindfulness of the body conditioning happiness / Awakening

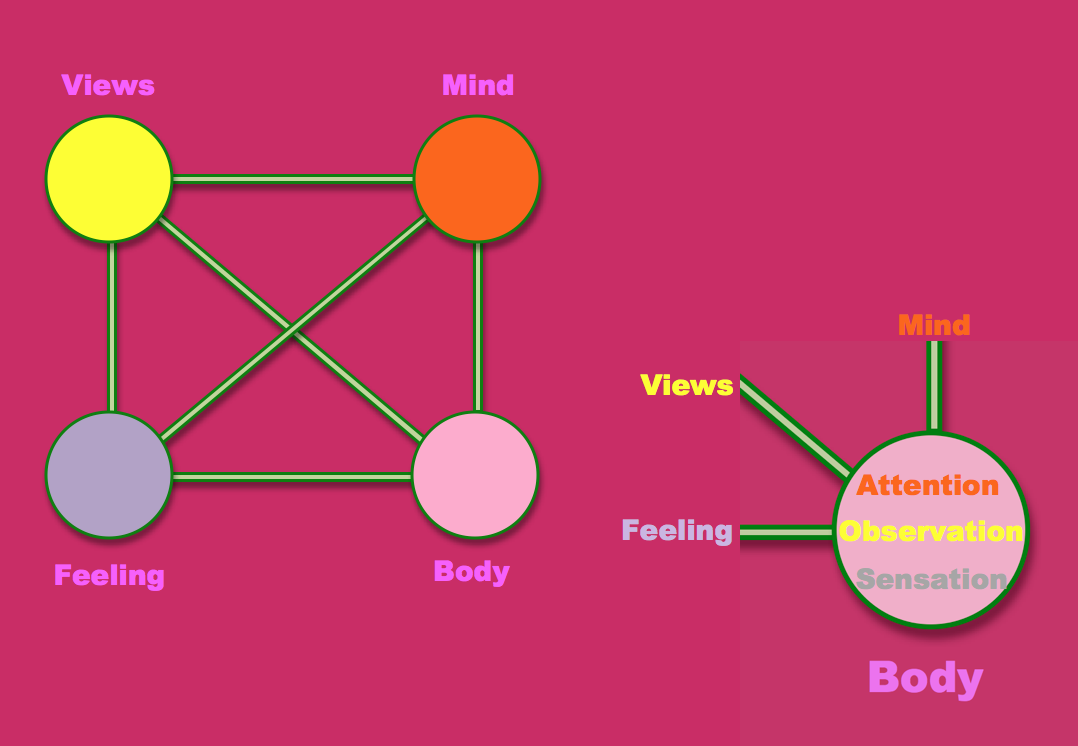

Body

When we are trying to transform our body and the objects of the world to be sources of happiness, we need to bear in mind that when the condition of ‘body’ is in place—as it always is, it affects feeling, mental states and views—contributing towards Awakening or suffering in the future, through the processes of sensation, attention and observation

SENSATION

Firstly, there is sensation. The body (kaya) conditions feeling as physical feeling (kayika vedana) or sensation,[5] thus:

Body —–Sensation—–> Feeling

So, we need to ask ourselves; ‘What sensation leads to happiness, and what to suffering?’

Sensation that leads to happiness

By taking care of our body, by looking after it well, by savouring our experience in the moment,[6] by taking care of our posture, by moving with grace and poise, by spending time in natural environments and by seeking out aesthetic experiences, we ‘maximize’ the pleasure that comes from sensory experience for ourselves. And by being careful when we are dealing with the bodies of others by looking after them too, not causing them harm, we ‘maximize’ the pleasure that comes from sensory experience for others. Thus, we practice Mindfulness of the Body.[7]

Sensation that leads to suffering

When we don’t take care of our body, don’t look after it well, don’t savour our experience in the moment, don’t take care of our posture, when we hold our body awkwardly or move it unnaturally, when we remain in cramped unaesthetic conditions, we ‘maximize’ the suffering that comes from sensory experience for ourselves. And when we aren’t careful when we are dealing with the bodies of others by not looking after them, causing them harm, we ‘maximize’ the suffering that comes from sensory experience for others. Thus, we are unmindful of Body.[8]

ATTENTION

Secondly, there is attention. Another way in which the body and tangible objects in the world condition Awakening is in the way they influence the mind in creating a particular quality of attention, for instance, meditative concentration (samadhi) or distraction, thus;

Body / World —–Quality of Attention—–> Mind

The quality of attention that we can muster will influence the happiness that we can bring to the world. This attention has three aspects.

- Firstly, if our project is to bring happiness to ourselves and others we need to be thoroughly involved with that project with the whole of our psyche, each part related to the whole, there being a congruence between what we say, what we do and how things are; our emotions, thoughts and attention to reality are all going in the same direction; when samadhi is present the thought, emotionand attention of the person is all oriented in a single direction, without force.[9] This is the aspect of integration.[10] Much of the time we are un-integrated; saying one thing and doing another. However, through mindfulness practice over a number of years, we develop greater self-knowledge and self-possession, become more congruent between our intentions and actions, and begin functioning as a ’smoothly-working whole.’[11] We view our body as a support for growth, caring for it. We don’t allow unconscious familial or cultural conditioning to dominate our character. Weaknesses are owned. Feelings acknowledged. Fears relaxed. Responsibilities are seen and supportive conditions cultivated. When we are integrated, we know when a part of ourselves is ‘going off-piste.’

- Secondly, our direction, in parallel with being wholehearted, needs to be skilful. True integration has the quality of integrity about it; we are morally upright in the sense of being honest, morally courageous and straightforward;[12] symbolically represented by the meditation posture, but also reliable, outward-looking, other-oriented, kind, aware; we include others in our decisions.

- The third aspect is being able to consistently maintain our focus; it is crucial if we are to bring happiness into the world that we are able to choose to place our mind on an object and keep it there; the best intentions to do ‘good’ will be of little use if we cannot concentrate on what we are doing. This one-pointedness of mind is represented by the Pali term citt’ ekagatta and is present as a (dhyana) factor in all four dhyanas.

When all three of these aspects are present, we possess what the Buddhist tradition calls samadhi, meditative concentration in this particular sense. Only then will they be able to stay focused on the goal of Awakening.[13]

Mindfulness is supportive to integration because;

- mindfulness is the quality that apprehends whatever is the case; it sees when a state leads to happiness; it ‘takes hold’ of it when it does; and it ‘lets go’ of it when it leads to suffering

- it does this with every pertinent condition (i.e., all four foundations of mindfulness)

The same principle applies in meditation theory and practice; samadhi is developed by intelligently managing our relationship to the objects of our attention. We try to establish a comfortable focus on whatever meditation object we choose, along with the ability to smoothly move our focus to other ‘objects’ (within the broad picture of our meditation practice) when they need attention, as we might do between members of a group.

In mindfulness we can do one thing at a time, bringing our attention into the present moment. When we wash the dishes, we just wash the dishes. We focus as completely as we can on the experience; on how the water feels; on the sensations in our hands; on the changing temperature as we move our hands from the warm water to the colder air; on whatever sounds we can hear; on how we feel as we work; on any thoughts that are present. We try to be as happily absorbed in and mindful of the experience as we can, whether we are walking, chewing a raisin, whatever our experience is.

In this way we ‘collect ourselves’ around the experience: developing samadhi. We ‘turn up’, waking up to the experience’s relevance for our lives. On a simple, but not trivial, level we wake up to the fact that we are here, and that our (AND other people’s) experience matters. And often, the fewer things we try to pay attention to at any one time, the easier it will be to focus on whatever is in front of us.

The way that our body is, and the configuration of objects in the world, both have a bearing on our ability to pay attention, in meditation and outside it.

The way that our body is

Various factors support meditative concentration, in the sense of samadhi. How our body is important in this process, and key to meditation practice.

Meditation posture

In the Satipatthana Sutta the monk is instructed to find a suitable place to meditate, away from the hurly-burly of everyday life; in the Buddha’s day this would mean going into the forest, to the foot of a tree, or an empty place, and setting up in the traditional cross-legged meditation posture.

Seated meditation posture represents the ideal and simplest situation in which to develop mindfulness; it supports the mind to be alert, and conditions for the body to be relaxed and vital.

Although it is routine to consider meditation posture solely in terms of the bodily position one adopts for meditation, while ones’ bodily position is important, I prefer to view meditation posture more broadly, as the overall background ‘structure and energetic state’ of the body, that facilitates care, mindfulness and awareness towards oneself and others. In this sense taking an Epsom salt bath or attending a gym session may be seen as helping meditation posture in this broader sense, to the extent that it does so.

Both inside and outside of meditation practice, vitality and relaxation in the body are essential to the project of delivering happiness and well-being. If our bodily state supports our mind and emotions in meditation as well as in life, it will be easier to concentrate; when we get up from our meditation this concentration will be readily available to direct towards our compassionate activities. When our body is uncomfortable or our posture unsupportive, we are likely to be distracted from our goal. If we do not get our body into a reasonable state, niggling discomforts will divert our attention from the meditation object, and our attention will be split.

The configuration of ‘objects’ in the world

The quality of our attention is frequently correlated with the number of ‘objects’ in the world that are demanding it; if we have too many things to think about at any one time our attention can becomes scattered, our mind hard to focus.

At the same time, we need to maintain a broad overview of everything needing our attention, having too few concerns can be a problem too. In group interaction, it is often claimed that the ideal group number is seven; fewer than seven and people can feel exposed, conflict too is more likely; with fifteen in a group individuals can feel unseen and unacknowledged and disengage. Having a moderate number of ‘objects of attention’ to focus on, and move between—say seven, allows not only for a more comfortable focus on individuals but also for a breadth of awareness of the group. This same principle applies to our meditation practice, in terms of our focus on and broad awareness of the objects of our experience.

Attention that leads to happiness

When we practice Mindfulness of the Body—in everyday mindfulness practice and in formal meditation, we are essentially doing three things in tandem:

- Being aware of sensation as outlined above.

- Being aware of and managing the way that our body is and also the configuration of objects in the world that we are engaging with, so that our attention is bright, awake, easily focused, wholehearted, engaged, receptive, steady, in fact it possesses all of the qualities of the dhyanas.

- Carefully observing the objects of our experience, so that our Views accurately reflect what is in front of us.

We cultivate this quality of attention in the mindfulness of breathing meditation practice, through limiting our focus to the sensations and movements of our breath, whilst maintaining a broad ‘out-of-focus’ awareness of the rest of our experience. In daily life we try to do one thing at a time, mindfully. Over time, through such practices, we gradually ‘collect ourselves together’ becoming more integrated; our actions more consistently skilful, and thus productive of happiness for ourselves and others.

Attention that leads to suffering

When we don’t practice Mindfulness of the Body, and so are;

- Unaware of sensation as outlined above.

- Unaware of and not managing the way that our body is and not taking in the configuration of objects in the world that we are engaging with. Our attention is dull, sleepy, easily distracted and fickle, turbulent; in fact, it possesses all of the qualities of the hindrances to meditation.[14]

- Unable to carefully observe the objects of our experience, so that our Views don’t accurately reflect what is in front of us.

We don’t cultivate this quality of attention in the mindfulness of breathing meditation practice, but instead we move from one distraction to another, feeling stressed; our life unmanageable. In daily life we try to do many things at one time, and unmindfully. Over time, through lacking a mindfulness practice, we gradually become even more unintegrated; our actions more consistently unskilful, and thus productive of suffering for ourselves and others.

OBSERVATION

Thirdly, there is observation. The body and tangible objects in the world condition our views through the process of observation.

Body / World —–Observation—–> Views

Mindfulness has been viewed as paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgementally. With mindfulness we basically observe our experience, knowing what we are experiencing; looking at what is conventionally called a chair we know that we are looking at a chair, that is, we label our experience correctly. And likewise, we recognize our inner states, our feelings, for what they are; we clearly comprehend our situation. Not only this, we know the nature of that experience; we know that the chair or the mental state is not fixed, but impermanent and that we cannot therefore rely on it to give us lasting satisfaction. The more keenly we observe our experience, the more honed our view of that experience will be, and the more likely our clear comprehension will deliver the happiness and well-being we are looking for.

Observation is an important practice because it helps ensure that our views are in line with how things are, rather than being opinion or dogma, unverified by experience.

Observation that leads to happiness

When we carefully observe everything about our experience in a way that leads to clear comprehension of that experience, we establish a view that is in line with reality and thus is productive of happiness for ourselves and others.

Observation that leads to suffering

When we fail to observe our experience carefully enough, we end up holding wrong views about that experience which lead to suffering for ourselves and others.

The chapter goes on to explore how the Foundation of Feeling conditions the others.

[1] Dennis Greenberger, Christine A. Padesky. (2015) Mind Over Mood: Change How You Feel by Changing the Way You Think. Second edition. Guilford Press. p7.

[2] ‘One who understands the totality clearly with wisdom from all angles (of whatever is manifesting) or who knows distinctly has sampajanna’ Samantato pakarehi pakattham va savisesam janati ti sampajano. Digha Nikaya Tika 2. 376. Source: https://www.vridhamma.org/research/The-Four-Sampajanna

[3] The Buddha did not mention these four sampajannas in the sutras; they are found in the Theravada commentaries (Atthakatha).

[4] The Theravada view concerning the four sampajannas is different from the one I express above: rather than identifying Wisdom with a deep understanding of Conditionality—as I do above, they identify it with realizing impermanence and the other laksanas and tie the four sampajannas in with this view: ‘If we analyse each of them, we find that they are not separate from one another but have the same goal, the realization of anicca (anicca-bodha, literally, impermanence-Awakening). Anicca-bodha is our real purpose (satthaka). It is beneficial (sappaya) for us and is the domain (gocara) of our meditation, leading to right understanding (asammoha), that ultimately results in the final emancipation – nibbana.’ … Also, ’Maintaining the continuity of the thorough understanding of impermanence based on vedana (sensation) is called sampajanna.’ The Four Sampajanna. Vipassana Research Institute. Accessed 8 March 2019.

https://www.vridhamma.org/research/The-Four-Sampajanna

However, I argue that Conditionality is the deeper truth, upon which the three laksanas rest.

[5] Sensation is the feeling that we experience through possessing a body equipped with five senses and is the first arrow that the Buddha talks about in the Sallatha Sutta. SN 36.6.

[6] As with the raisin exercise.

[7] We also avoid pursuing sensory experience in a way that leads to craving and attachment, which causes harm for ourselves and others, but this comes under the section on ethical feeling.

[8] We also do pursue sensory experience in a way that leads to craving and attachment, which causes harm for ourselves and others, but again, this comes under the section on ethical feeling.

[9] Sam– meaning ‘complete / the same’ and adhi ‘direction.’

[10] Integration; from the Latin integer, intact.

[11] We recognize what is true; the process by which we recognize a thing as such is called ‘apperception’ (Pali: sanna; Sanskrit: samjna). This is how we construct our view of the world. For instance, recognizing both the latest model of our favourite phone and the fact that we want to be happy, we put the two ideas together and construct a view that we will only really be happy once we have upgraded our phone. If however, we bring mindfulness to our apperceptions and our views and ask ourselves if they are true, we have the opportunity to make our views and apperceptions more accurate; and conducive to alleviating suffering. For instance, before practising the Mindfulness of Breathing meditation we might think that we are quite mindful; however, once we attend to the simple experience of the breath and see how our mind easily wanders off we realize that we are not quite as mindful as we had previously thought. Through mindfulness our apperceptions of how mindful we are improve, until we realize that we really have to become more mindful; thus fulfilling the aim of the practice.

[12] Integrity is ‘the quality of being honest and having strong moral principles.’ ‘Integrity.’ Oxford Dictionaries.

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/integrity

Synonyms for integrity include honesty, uprightness, probity, rectitude, honour, honourableness, upstandingness, good character, principle(s), ethics, morals, righteousness, morality, nobility, high-mindedness, virtue, decency, fairness, scrupulousness, sincerity, truthfulness, trustworthiness, our attitudes, utterances and behaviours being supportive of the general good.

[13] ‘Samadhi is present in one who gains concentration, gains one-pointedness of mind, having made release (Nirvana) the object’, and is ‘seen’ in the four dhyanas. Samyutta Nikaya 1670-1.

[14] For Hindrances see Chapter 10.

Users Today : 40

Users Today : 40 Users Yesterday : 23

Users Yesterday : 23 This Month : 498

This Month : 498 Total Users : 13925

Total Users : 13925