Below is an excerpt from my forthcoming book…

© Mahabodhi Burton

6 minute read

This excerpt is taken from the chapter ‘Kindness front and centre‘ and follows on from Mindfulness and the Five Paths.

Remembering loving kindness as a central aspect of the path

When Sangharakshita gave a seminar on the Precious Garland[1] in 1976 he laid a foundation for what was to become his central exposition of the Dharma,[2] namely that the path consisted of five elements:

- Integration

- Positive Emotion

- Spiritual Death

- Spiritual Rebirth

- Spiritual Receptivity[3]

Where he links integration with mindfulness and positive emotion with the four right efforts. As we saw earlier, the Path of Accumulation consists of:

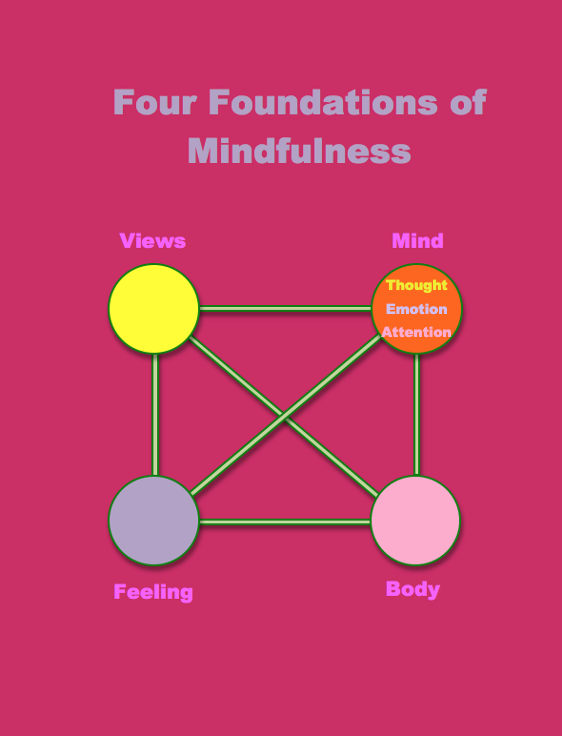

- The four foundations of mindfulness, which represent establishing the appropriate domains of mindfulness

- The four right efforts,[4] which represent energy being put into 1) overcoming the four foundations as sources of suffering and 2) establishing them as sources of happiness

- The four bases of success,[5] which represent the states of meditative concentration that are achieved when our efforts have been successful[6]

Sangharakshita is concerned to dispel a common view that one only has to bring mindfulness to a situation for it to naturally resolve. He points out that, because the four right efforts follow on from the four foundations of mindfulness in the teaching of the Five Paths, this indicates that not everything can be achieved by force of mindfulness, the effort to develop the skilful also needs to be involved.

‘In a way (the Five Paths) goes a bit against the Theravada teaching, which does seem, perhaps one can say, a bit dry; if you just try to do everything by force of mindfulness, everything by force of awareness: so that isn’t the Mahayana path, clearly.’[7]

Mindfulness on its own has an effect, he says, although it is not a very great effect, compared to when it is combined with the four right efforts.[8]

‘So, it’s as though, when one is practising simply awareness, and simply mindfulness, you are just watching, you’re just the observer. The mere fact of your watching, the mere fact of your observing–body, feelings, thoughts, and thinking as it were of higher things. This has its overall effect, but it’s not a very great effect, and not a very deep effect. …. But when you’re practising the four great efforts you are ‘doing’ something in a much more radical way. You’re bringing about much greater changes. You’re actually making a positive direct effort to throw out the unskilful, to bring in the skilful to an ever greater and greater degree. So this is a much more intensive form of practise.’[9]

Linking the four right efforts with loving kindness or metta:

‘In the case of the metta, you are bringing into existence skilful mental states. So, you could say that the metta was a form of right effort, or you could say it was a form of one of the four great efforts.’[10]

Sangharakshita says that if you want just one word for the sequence: four foundations of mindfulness; four right efforts:

It would be ‘Mindfulness, Positive Emotion.’

In the Questions of King Milinda, mindfulness was best viewed as awareness being applied to whatever leads to happiness. Metta therefore is necessary to ’complete the picture’ of mindfulness. It bears repeating that the bottom line for living beings is that they desire happiness and do not want to suffer. If we wish to bring this about, we essentially need two things. We need to want happiness for ourselves and others, which is metta. And we need to know how to bring it about, and this is where mindfulness comes in. The teaching of the Five Paths therefore remembers loving kindness as a central aspect of the path.

Balancing the Theravada attention to wisdom with faith and devotion

In the Path of Preparation, we find an emphasis on balancing those spiritual faculties necessary to attain Nirvana and fully developing them into powers. We might suspect the Five Paths are a conscious corrective to the Theravadin interpretation of the Satipatthana Sutta because the Theravada tends to focus rather narrowly on developing wisdom, whereas in the Mahayana the practice of devotion is equally important: by fully developing both faith and wisdom on the Path of Preparation, this Theravadin imbalance is overcome.

‘Nirvana in ten minutes’ – Talk at Manchester Buddhist Centre, circa 2013, 26 minutes.

‘Nirvana in ten minutes’ – Talk at Manchester Buddhist Centre, circa 2013, 26 minutes.

Maybe ‘balancing’ is not quite the right word: we do not aim to balance spiritual faculties in the way that yin balances yang in Chinese medicine; or that grey is the halfway point between black and white. Sangharakshita talks of how the Middle Way is not some mediocre average, but a ‘higher third,’ just as faith and wisdom combine in a higher third.

‘The process of reaction in a progressive order (i.e., the Spiral Path) constitutes the basic principle of the Path taught by the Buddha … As the embodiment of this ’spiral’ principle, moreover, and not because it represents a “golden mediocrity” of the Aristotelian type or a half-hearted spirit of compromise, the Path receives its primary designation as the Middle Path or Way.’[11] (My emphasis)

The idea of balance delivers a rather tepid account of the spiritual life, whose aim is to take on the most difficult of tasks, including the challenge of old age, sickness and death. It won’t help anyone to hold the idea that they need to ‘tone down their strengths’ as they ‘raise up their weaknesses’ until both are at the same level. For instance, if suppose we are a man, the idea that we need to become ‘a bit less masculine and a bit more feminine’ is not helpful: the world needs powerful male energy just as much as it needs sensitive female energy: otherwise, the roads don’t get built. The true individual is robust yet sensitive.

To the extent that we do have strengths, we need to lead with them, because this is where we are at our most skilful, in the sense of being the most ‘fluid;’ and because it is through these skills that we benefit others the most. People’s strengths are very different: the intellectual ‘swims’ most easily in the world of concepts; the artist is fluid with language, symbol and emotion; the yogi’s true strength lies in working with their tangible physical experience; and the general is competent at practical organisation: he knows well how to marshal his troops. At the same time, it will be of general benefit if each individual tries to bring their weaker faculties up to the level of their strengths.

In society and religion, the cultivation of one human faculty is often promoted at the expense of others, resulting in the lopsided development of its members, which impedes their rounded human development and thus their spiritual progress:

- Theistic religions who promote blind faith elevate emotionover reason

- Secular society promotes a scientific materialist worldview and thus elevates reason over emotion

- The division of labour in capitalist society encourages specialisation

- The Hindu castesystem restricts religious practice to its higher castes

Buddhism on the other hand, tries to bring all of the faculties of the individual into play and transforms them into those of a Buddha: a scholar might be encouraged to engage in ethical livelihood; an artist to engage in dharma study; a manual worker to reflect on their experience; a yogi to participate in the community; and a general to work for peace. To the extent that a person’s livelihood, societal position or religion encourages lopsided development, Buddhism suggests that they move beyond the confines of those positions.[12]

Mindfulness the spiritual faculty appreciates the urgency of developing each spiritual faculty into a power, and thus to oversee their overall balanced development (to the extent that any spiritual faculty is not developed to be a power, suffering will ensue.) Each spiritual faculty is developed to be a power largely through concentrating on a particular aspect of Buddhist practice.

- Meditative concentration – Meditation practice

- Ethical robustness – Ethical livelihood

- Faith – Ritual and devotion

- Wisdom – Study and reflection

The chapter goes on to explore The Five Paths as Cumulative.

[1] https://www.freebuddhistaudio.com/texts/seminartexts/SEM128_Precious_Garland_-_Unchecked.pdf

[2] Called at different times; his ‘System of Meditation’; ‘System of Spiritual Practice.’ See Sangharakshita and Subhuti. Seven Papers. Second Edition (2.01). Download text at https://bit.ly/sevenpapersdownload

[3] To the four stages of the System of Meditation, Sangharakshita recently added a fifth, Spiritual Receptivity, which he links with the ultimate stage of the Five Paths: ‘No More Learning / Spontaneous Compassionate Activity.’

[4] The four right efforts consist of: 1) the effort to eradicate unskilful mental states, 2) the effort to prevent them from arising, 3) the effort to cultivate skilful mental states, 4) the effort to maintain those already arisen.

[5] Or ‘bases of power.’ The four bases of such power are meditative concentration (samadhi) due to: 1) Intention / purpose / desire / zeal (chanda), 2) Effort / energy / will (viriya), 3) Consciousness / mind / thoughts (citta), 4) Investigation / discrimination (vimamsa). See Bhikkhu Bodhi (trans.) (2000). The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya. Boston: Wisdom. ch. 51, p1718-49; Ajahn Brahm (2007) Simply this Moment!. Perth: Bodhinyana Monastery. p394; Rhys Davids & Stede (eds.) (1921-5) The Pali Text Society’s Pali–English Dictionary. Chipstead: Pali Text Society. p120-1; and the ‘Iddhipada’ entry in Wikipedia. In the Pali Sutras, we see metaphorical descriptions of the results of the development of the iddhipadas: ‘When the four bases of spiritual power have been developed and cultivated in this way, a bhikkhu wields the various kinds of spiritual power: having been one, he becomes many; having been many, he becomes one; he appears and vanishes; he goes unhindered through a wall, through a rampart, through a mountain as though through space; he dives in and out of the earth as though it were water; he walks on water without sinking as though it were earth; seated cross-legged, he travels in space like a bird; with his hands he touches and strokes the moon and sun so powerful and mighty; he exercises mastery with the body as far as the brahma world.’ Pubba Sutta, SN 51.11

[6] Sangharakshita argues that the Path of Accumulation consists of three degrees of intensity; the practice of mindfulness alone helps in slowing you down, but in the Five Paths; ‘it’s not conceived of that (the four foundations of mindfulness) are practised right at the beginning to the full. Though no doubt as one gets onto other stages and levels of practice one will be able to practise mindfulness more. In other words, this level of practice of mindfulness represents as far as you can get with mindfulness, without invoking any other type of practice, as it were.’ I would argue that the four foundations of mindfulness are practised all the way to Nirvana, and that metta is an aspect of that process from start to finish, but they need to be interpreted correctly.

[7] Sangharakshita. (Padmaloka, 1976) Mind in Buddhist Psychology – Unchecked (seminar) p47. Free Buddhist Audio. Download complete text at,

https://www.freebuddhistaudio.com/search?s=0&r=10&b=p&q=mind+in+buddhist+psychology&t=audio

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid. p48.

[11] Sangharakshita. (1991) The Three Jewels: An Introduction to Buddhism. Windhorse. p110.

[12] See Chapter 9, ‘The Pattern of Buddhist Life and Work’, in Sangharakshita (1998) What is the Dharma: The essential teachings of the Buddha. Windhorse. p184ff.

Users Today : 65

Users Today : 65 Users Yesterday : 23

Users Yesterday : 23 This Month : 523

This Month : 523 Total Users : 13950

Total Users : 13950