Below is an excerpt from my forthcoming book…

© Mahabodhi Burton

10 minute read

This excerpt is from the chapter ‘Augmentative Conditionality; The Spiral Path‘ and it follows on from an exploration of the early stages of that path.

Mindfulness of mind

As well as cultivating the appropriate creative emotional response to feeling, the monk works the other aspects of his mind so that they too conduce to skilfulness; he trains his attention to be sharp and ever present. And through reflecting on the veracity of his thoughts, he trains them to be in line with reality and thus to fostering universal well-being.

Thought and reflection

In the Dvedavitakka Sutta the Buddha says;

‘Whatever a monk keeps pursuing[1] with his thinking and reflecting, that becomes the inclination of his mental states and emotions (his citta)’[2]

We probably all recognize that the more we reflect upon an idea, the more that thought becomes a habit: the Buddha warned the Kalama people against adopting ideas just because:

- They have heard them repeatedly

- They have been handed down in a tradition or lineage

- Of hearsay

- They see a scripture as authority

- Of sophistry or logical inference

- Of prolonged consideration

- Of getting carried away by a view they identify with [alternatively, ‘nor on indulgence in the pleasure of speculation’]

- Someone made a plausible impression on them [alternatively, ‘nor on (something that) looks plausible’]

- They have respect for a certain spiritual teacher[3]

He taught instead that only when they know in their hearts that an idea leads to well-being and not to suffering should they adopt it: the list above indicates that the reason why we adopt one idea over another is often more down to habit, emotion or association than to such conscious examination.

Vitakka and vicara

Two Buddhist terms are in common use which are associated with thought: vitakka (Pali; Sanskrit: vitarka) and vicara (Pali and Sanskrit.) Opinions differ as to how best to translate them: many suggest ‘thinking of’ and ‘thinking about’ respectively. In my own view, they are best translated as ‘opining’ (in the sense of holding an opinion) and ‘reflecting’[4] (however, as they also refer to responses to imagery, in this case they might be rendered ‘visioning’ and ‘imagining’.) Some, like Leigh Brasington,’[5] argue that the terms are synonymous in that they both mean ‘thinking: I think this reasoning is lazy; some argue that in the first dhyana each is only concerned with attention,[6] but there is good reason to think otherwise: the most cogent explanation is that vitakka represents the capacity of the mind to turn towards a view (the Pali vi- means ‘split or separate’–as in di-vi-de–and takka means ‘to turn:’ it being related to the English word torque. Vitakka is that faculty which isolates one view from other views and then turns the mind to it; it is essentially the process of holding a particular view; importantly, we most frequently turn our mind to those things which we believe will make us happy: often relationships, status, possessions. Likewise we isolate one image from other images and holding that in our mind (as significant:) this is how advertising works.

Vicara, on the other hand, is the process whereby we think about or dwell upon those ideas and images,[7] in the sense that we examine, evaluate and consider them; explore them from different angles; ask if they are true; compare them to other views;[8] with images it is the same: we try and work out if following a certain dream or vision will help us.

Mental Proliferation: Papanca

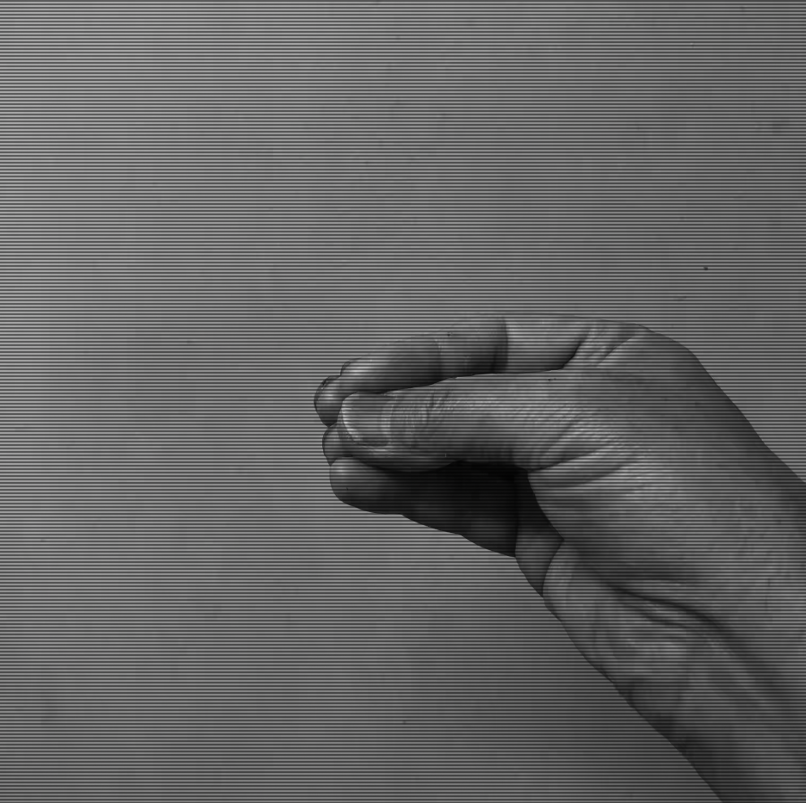

Vitakka and vicara are viewed in the Abhidharma as ‘indeterminate mental factors:’ this means that they can be either skilful or unskilful. Unskilful opining (vitakka) involves holding the mind to a viewpoint which inheres suffering, such as the belief that obsession with certain objects of refuge that are subject to impermanence will not cause suffering; unskilful reflection or papanca (Pali; Sanskrit: prapanca,) also known as ‘mental proliferation,’ involves turning that refuge over in one’s mind, delighting in it, relishing it, in a way which only makes the viewpoint stronger. The Buddha may have illustrated papanca by stretching out the five fingers of his hand (the Pali panca literally means ‘five’,) indicating how the mind unconsciously ‘spreads out’ as it proliferates: either about objects of desire, or, in the case of anxiety, around fearful scenarios.

For instance, we might be trying to cultivate loving kindness towards a friend, yet suddenly our mind turns towards a holiday we are planning later in the year, and we start dwelling on all the fun experiences we expect to have: our concern for our friend decreases and our desire for our holiday increases.

Or, if we are practising the difficult person stage of the metta bhavana we might unconsciously slip into proliferating around the harms our enemy has done to us: thus we increase our aversion towards them rather than cultivate care. In these examples, it is papanca that fosters the unskilful states of desire for sense experience and aversion.[9]

In the Dvedavitakka Sutta above, when the monk frequently turns his mind (bahulamanuvitakketi) to the wrong view that material possessions can bring ultimate happiness, once he holds that view, if he unconsciously mulls it over (vicara as papanca,) this inclines his mind (citta) to the relevant unskilful mental state.[10]

Skilful reflection

Vitakka and vicara are also present in skilful mental states—an example being the higher state of consciousness called the first dhyana. Skilful vitakka involves holding in the mind a view which has a skilful outcome: such as the benefit to living beings of kindness and awareness; skilful vicara involves the creativity involved in consciously reflecting on and ‘drawing together’ the conditions necessary to bring that about, which we might represent not by stretching out the five fingers of the hand but by drawing the fingertips together into a cone.

The opposite of proliferation is not really ‘non-proliferation:’ which only indicates an absence of ‘spreading out;’ the noun ‘decrement’ means ‘a process of becoming smaller or shorter’ rather than ‘increment,’ which means ‘a process of growing larger and longer:’ through reflection we reduce the things we are dealing with to the most essential and important. We ask questions like: ‘What is the relevance of this to the rest of my life?’ ‘How important is this in the scheme of things?’ coming eventually to the ultimate question, ‘Does this lead to happiness or suffering?’

Papanca[11] is neither conscious nor directed, whereas skilful reflection is conscious, directed and aimed at cultivating the truth: thus, leading to the cultivation of skilful mental states and therefore to a happy outcome for ourselves and others. This is the mode of vicara that we normally understand by reflection.

The first dhyana is a state in which the mind has not yet gone into silent absorption: that comes in, the second dhyana. It is a place where the person is still thinking but that thought is constructive: it is devoid of views where the person relies on the world of sensual experience; and it is devoid of all views that lead to unskillful mental states. So what is the thought about?

I think that the thought of the first dhyana is all about building up a firm and lucid conviction in the truth and efficacy of skilful action. The Buddhist meditator has been compared to the scientist (of the mind:) in a way they try out mental states until they find the ones that work: in the sense of delivering happiness. Thus the experiences of spiritual rapture and happiness arise in the first dhyana only because the meditator sees a clear way to universal happiness that doesn’t involve relying on sensual experience or unskilful mental states, but instead relies on the renunciation of sense desire and the cultivation of skilful mental states.

The chapter goes on to explore the higher reaches of the Spiral Path.

[1] The Pali phrase bahulamanuvitakketi means something like ‘frequent mind turning’ (bahula + manas + vitakka).

[2] In Pali: ‘Yannadeva bhikkhave bhikkhu bahulamanuvitakketi anuvicareti tatha tatha nati hoti cetaso.’ Thanissaro translates citta as ‘awareness’, but it is more accurately the monk’s mental states, which include his thoughts, emotions and attention.

[3] ‘The Buddhas Advice to the Kalamas.’ Ratnaprabha = Robin Cooper: writings on Buddhism. 22 June 2020.

https://ratnaprabha.net/2020/06/22/the-buddhas-advice-to-the-kalamas/

[4] There is debate going on amongst scholars within the Buddhist tradition concerning the precise meaning of the terms vitakka and vicara. While they are frequently translated respectively as ‘initial thought’ and ‘sustained thought:’ where the former is understood as ‘thinking of’ and the latter ‘thinking about,’ some wish to translate them as ‘initial and sustained attention’, following the logic that meditation often involves sustained attention upon the breath. My argument, however, is that the true object of the mindfulness of breathing meditation practice is mindfulness itself: the breath being only the means to recognize how mindful one is in a particular moment.

[5]Leigh Brasington argues that the use of these two terms does not indicate two aspects of thinking but are an example of ‘synonymous parallelism’, a rhetorical device that occurs frequently in the Buddhist suttas, as in the phrase ‘They pervade, drench, saturate and suffuse this very body with the rapture and happiness born of seclusion (my italics).’ The above phrase is obviously poetical in nature rather than technical. Even the simple idea of holding a view already contains within it two aspects of mind: the view itself and the mind holding it: these I argue correspond to manas and citta: and therefore to vitakka and vicara. See Brasington, L. (2015) Right Concentration. Shambhala.

[6] The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism has: Vitarka. (Pali. vitakka) In Sanskrit, ‘thoughts,’ ‘applied thought,’ or ‘applied attention.’ … Although etymologically the term contains the connotation of ‘investigation,’ vitarka is polysemous in the Buddhist lexicon and refers to a mental activity that could be present both in ordinary states of consciousness as well as during meditative absorption (dhyana). Generically, vitarka can simply denote thoughts, and specifically ‘distracted thoughts,’ as in the Vitakkasanthana Sutta. In ordinary consciousness, it is perhaps best translated as ‘applied thought’ or ‘initial application of thought’ and refers to the momentary advertence toward the chosen object of attention. Vitarka is listed in the Abhidharma as an indeterminate mental factor, because it can be employed toward either virtuous or non-virtuous ends, depending on one’s intentions and the object of one’s attention. In meditative absorption, vitarka is one of the five constituents (dhyananga) that make up the first dhyana and is perhaps best translated in that context as ‘applied attention’ or ‘initial application of attention.’ In dhyana, vitarka involves directing one’s focus onto the single chosen meditative object. According to the Pali Visuddhimagga, ‘applied attention’ is like a bee flying toward a flower, having oriented itself toward its chosen target, whereas ‘sustained attention’ (vicara) is like a bee hovering over that flower, having closer contact with and fixing itself upon the flower. ‘Vitarka.’ Buswell Jr., Robert E. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

[7] The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism has: Vicara. In Sanskrit and Pali, ‘sustained thought,’ ‘sustained attention,’ ‘imagination,’ or ‘analysis.’ … Although etymologically the term contains the connotation of ‘analysis,’ vicara is polysemous in the Buddhist lexicon and refers to a mental activity that can be present both in ordinary states of consciousness and in meditative absorption (dhyana). In ordinary consciousness, vicara is ‘sustained thought,’ viz., the continued pondering of things. It is listed as an indeterminate mental factor because it can be employed toward either virtuous or non-virtuous ends, depending on one’s intention and the object of one’s attention. Vicara as a mental activity typically follows vitarka, wherein vitarka is the ‘initial application of thought’ and vicara the ‘sustained thought’ that ensues after one’s attention has already adverted toward an object. In the context of meditative absorption, vicara may be rendered as ‘sustained attention’ or ‘sustained application of attention.’ With vitarka the practitioner directs his focus toward a chosen meditative object. When the attention is properly directed, the practitioner follows by applying and continuously fixing his attention on the same thing, deeply experiencing (or examining) the object. In meditative absorption, vicara is one of the five factors that make up the first dhyana. ‘Vicara.’ Buswell Jr., Robert E. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

[8] The Pali vicarati means ‘to go or move about in, to walk (a road), to wander.’ Vicara therefore means ‘investigation, examination, consideration, deliberation.’ From cara; ‘the act of going about, walking.’ Online Pali-English Dictionary.

https://dsalsrv04.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/app/pali_query.py?qs=Carati+

[9] The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism has: Prapanca. (Pali. papanca). In Sanskrit, lit. ‘diffusion,’ ‘expansion’; viz. ‘conceptualisation’ or ‘conceptual proliferation’; the tendency of the process of cognition to proliferate the perspective of the self (atman) throughout all of one’s sensory experience via the medium of concepts. … By allowing oneself to experience sensory objects not as things-in-themselves but as concepts invariably tied to one’s own perspective, the perceiving subject then becomes the hapless object of an inexorable process of conceptual subjugation: viz., what one conceptualizes becomes proliferated conceptually throughout all of one’s sensory experience. … Everything that can be experienced in this world in the past, present, and future is now bound together into a labyrinthine network of concepts, all tied to oneself and projected into the external world as craving (trsna), conceit (mana), and wrong views (drsti), thus creating bondage to Samsara. ‘Prapanca.’ Buswell Jr., Robert E. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

[10] In the text the Buddha gives examples of sense desire, ill-will and harmfulness.

[11] Prapanca: the Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism has: By systematic attention (yoniso manasikara) to the impersonal character of sensory experience and through sensory restraint (indriyasamvara), this tendency to project ego throughout the entirety of the perceptual process is brought to an end. In this state of ‘conceptual non-proliferation’ (Pali. nippapanca; Sanskrit. nihprapanca), perception is freed from concepts tinged by this proliferating tendency, allowing one to see the things of this world as impersonal causal products that are inevitably impermanent (anitya), suffering (Sanskrit. duhkha), and non-self (anatman). The preceding interpretation reflects the specific denotation of the term as explicated in Pali scriptural materials. In a Mahayana context, prapanca may also connote ‘elaboration’ or ‘superimposition,’ especially in the sense of a fanciful, imagined, or superfluous quality that is mistakenly projected on to an object, resulting in its being misperceived. Such projections are described as manifestations of ignorance (avidya); reality and the mind that perceives reality are described as being free from prapanca (nisprapanca), and the purpose of Buddhist practice in one sense can be described as the recognition and elimination of prapanca in order to see reality clearly and directly. In the Madhyamaka school, the most dangerous type of prapanca is the presumption of intrinsic existence (svabhava). In Yogacara, prapanca is synonymous with the ‘seeds’ (bija) that provide the basis for perception and the potentiality for future action. In this school, prapanca is closely associated with false discrimination (vikalpa), specifically the bifurcation of perceiving subject and perceived object (grahyagrahakavikalpa). The goal of practice is said to be a state of mind that is beyond all thought constructions and verbal elaboration. The precise denotation of prapanca has been the subject of much perplexity and debate within the Buddhist tradition, which is reflected in the varying translations for the term in Buddhist canonical languages. The standard Chinese rendering xilun means ‘frivolous debate,’ which reflects the tendency of prapanca to complicate meaningful discussion about the true character of sensory cognition. The Tibetan spros ba means something like ‘extension, elaboration’ and reflects the tendency of prapanca to proliferate a fanciful conception of reality onto the objects of perception. ‘Prapanca.’ Buswell Jr., Robert E. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

Users Today : 76

Users Today : 76 Users Yesterday : 23

Users Yesterday : 23 This Month : 534

This Month : 534 Total Users : 13961

Total Users : 13961