Below is an excerpt from my forthcoming book…

10 minute read

This excerpt is from Chapter 8, ‘Mindfulness the Undiscovered Foundations,’ in which I explore the Four Foundations of Mindfulness (Pali: satipatthanas,) and here, ‘Mindfulness of Mental Objects (Pali: dhammas.)

I am particularly concerned to clarify this key section of the Satipatthana Sutta: current interpretations of ‘mental objects’ and ‘dhammas‘ have lacked conviction amongst commentators.

Views

I have arrived at ‘Views’ as my translation of dhammas, and this is how. Dhamma roughly is ‘what can be remembered’ or ‘what can be borne in mind’ (Pali: dharetabba), hence the translation of dhammas as ‘mental objects’ and sometimes as ‘phenomena.’[1] ‘Mental objects’ doesn’t tell us very much about what dhammas are, although two things we do hold in the mind are ‘concepts’ and ‘images.’

Buddhism teaches that we have not just five but six senses, with the mind being the sixth sense called manas. As humans we have evolved to make assessments about the world around us. These assessments can be at the level of thought, although prior to thought, evolution taught us the more gut-level instinctual response of fight or flight, where information resides at the visceral level on a ground of learned experience. According to Sagaramati, a view is a deeply ingrained attitude, not simply an opinion; it arises on one or all of Buddhism’s grounds for faith: reason, intuition and experience.

When we come across something that meets one of these criterion as a means either for survival, to avoid pain, or to bring joy and fulfilment, we don’t need to consciously make an effort to place that ‘mental object’ in our mind, it naturally gets stored there. In this way views naturally arise based upon a mix of feelings, gut instincts, and reasons; in fact, often it is emotion that plays the bigger role, only for us to later come up with rationalizations for the views we hold.

The process of bearing a mental object in mind, i.e. in the mind-sense manas[2] (Pali,) involves apperception or recognition (Sanskrit: samjna; Pali: sanna.) Through life we are taught the conventional conceptual meanings of concrete objects and abstract concepts: chair, desk, popularity. Once we know these as names, we can recognize them when we see them. But we also recognize images: a person’s face, a landscape, a painting, a visualized Buddha.

‘Although when manas is translated as ‘mind’ dhammas tends to be rendered accordingly as ‘thoughts’ or ‘ideas’, note that dhammas qua the object of manas as the sixth sense faculty refer not only to thoughts, ideas or concepts, but to mentality in its broadest denotation: dhammas are the objects when one, for instance, remembers, anticipates or concentrates on something. There are six modes of cognitive awareness and five physical sense faculties; anything else is dhamma.’[3]

The way that these ‘mental objects’ constellate in our minds into a perspective comes to be our worldview or belief system, within which certain ideas and images predominate in the moment. These ideas and images tell us what we really believe in; dictating our behaviour, no matter what we might think we believe, and make up our perspective.

View as mental perspective

Dhammas are to the mind-sense what visual forms are to the eye:[4] just as a visual perspective is formed when the eye looks through[5] a field of visual objects, a mental perspective or view forms when the mind-sense ‘looks through’ a field of mental objects (dhammas). As an illustrative example, a materialist who is also an optimist will likely imagine themselves enjoying various happy experiences in the forefront of their consciousness, whilst thoughts about traditional religious concerns including life after death will be pushed back into the background of their mind or be absent altogether. On the other hand, the political theorist who is pessimistic by nature will likely experience dystopian images of society in the foreground of their mind, with concerns about personal material comforts relegated more to the background. And based on each’s perspective, they act in the world appropriately: by amassing wealth or practising political activism.

The Pali word Dhamma (Sanskrit: Dharma) in Buddhism means The Truth or the teaching of the Buddha. A problem with this word being used cross-culturally—in Buddhism and Hinduism– is that is that where dhamma indicates ‘a way of seeing’, ‘the truth about things’, ‘what is (really) there’, what is seen is implicit in the worldview of the person doing the seeing; the Hindu understands Dhamma as the individual’s caste duty, within which the freedom and opportunities of the lower castes are restricted; the Buddhist understands it as the Buddha’s teaching leading to the alleviation of suffering for all sentient beings; two contradictory aims. Like the word ‘Truth,’ the word Dhamma necessarily means different things to different people, essentially reflecting their view of the world. When I talk about a Dharmic viewpoint I specifically mean the Buddhist one.

We cannot but have views. I render dhammas as ‘Views’ because through practicing Mindfulness of dhammas we bring mindfulness to the way that we see things, asking ourselves if our views conduce to Awakening or not. In the Satipatthana Sutta the Mindfulness of dhammas section contains five sub-sections, each of which expresses the Buddhist view in a particular area:

1) The five hindrances

2) The five constituents of the person

3) Fetters associated with the six sense bases

4) The seven factors of Awakening

5) The four Noble Truths

For instance, in the section on the five hindrances, we ask ourselves if we really see the mental states of sense desire, hatred and so on as hindrances to happiness; maybe we don’t. The key idea is that through mindfulness of dhammas we can shift our view from whatever it is presently to a Dharmic perspective (in the Buddhist sense) where we do see them as hindrances.[6]

It is by dwelling on Dharmic ideas and images; by reflecting on the validity of our perspective through Dharma study and reflection; by bringing to consciousness the concepts and images (i.e. mental objects) that we tend to dwell on that we can offer a critique of our views from a Dharmic perspective. But because emotion plays a key part in the construction of our views, if we are to satisfy that side of ourselves we need to find ways of influencing our emotions in a positive way around a Dharmic perspective, for instance through the regular submersion in aesthetics or by practising Buddhist devotion.

The whole context that we engage in is of key importance: it is through thoroughly ‘weaving our lives’ in and around Buddhist thoughts, Buddhist images and Buddhist social situations, that we come to site our mind more firmly within a Dharmic context.[7]

We tend to hold certain views simply because we have been brought up with them or we have come to feel comfortable with them (especially views about ‘the self’.) However, it is an open question as to whether ALL views are essentially views about happiness and well-being. I suggest that they are: each living being possesses a thirst (tanha) for fulfilment / completion[8] in their area of concern: whether they are a political animal or technology geek, their interest will in some way be linked to happiness, even if that is just taking up Scientism as an escape from the uncomfortable realities of life.

All views are strategies to reduce suffering; this doesn’t mean that everything comes down to psychology, it goes much deeper than that; the Buddha taught that all worldlings (Pali: puthujjana)[9] are mad; desperate to survive, to be happy, to feel like they understand what is going on even when they don’t, they come up with views inextricably tied up with all of the above.

The monk’s view, then, encompasses not just what he thinks he believes on a conscious level, but also his unconscious fears, hopes and desires (as indicated by the mental objects that dominate his mind). These all thrust concepts and images into his mind for him to consider, and they contribute towards his view. It is not what we think that mainly determines what we do, but our unconscious emotions, which our activities can mask. We might know that something is a good idea but we still cannot bring ourselves to do it because of our more dominant, and unconsciously held, views. If we believe at the unconscious level that we can’t live with our feelings all kinds of wonky and irrational actions might ensue which help us dampen them down.

Wisdom (prajna)

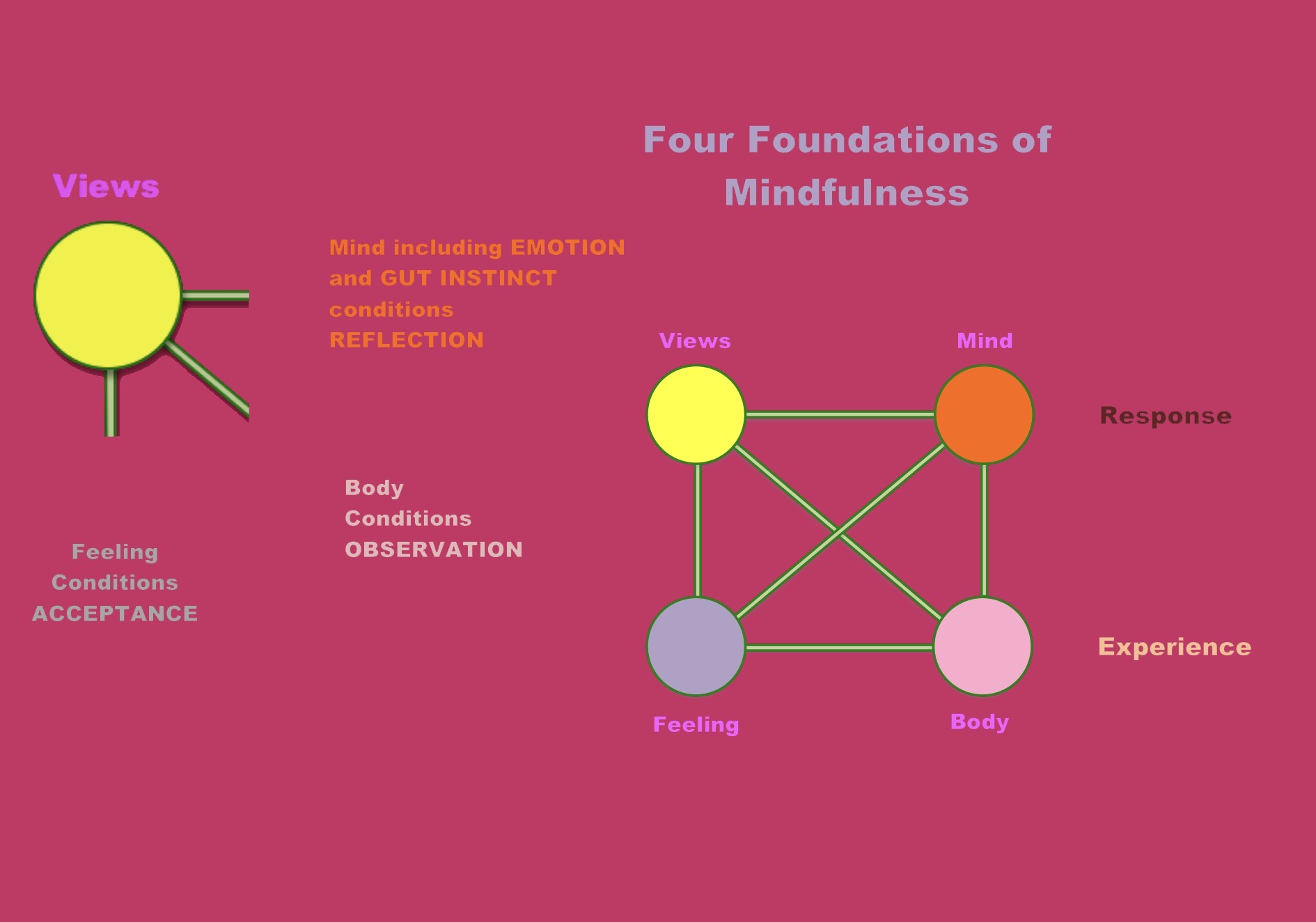

Views are simply the ‘operating perspective’ that a person holds at any one time. They give a person their ‘map’ of the world, out of which one set of actions flows rather than another. As such they are crucial, and primary. It is our views that determine how we act, and so we need to bring mindfulness to them to make sure that they are Right View, the view which according to the Buddha leads to happiness for ourselves and others. We arrive at Right View through three routes; we observe our experience, we accept the feelings we cannot change and we reflect upon our views; our views may be negatively affected by the fact that we don’t observe the world closely for what it is, don’t accept our experience when it is difficult and don’t reflect on our views (see diagram.)

In such cases our views are likely to lead to suffering. Mindfulness of Views works to transform all views, conscious and unconscious, to be conducive to Awakening. When this is the case, the monk can be said to possess wisdom or prajna.[10]

[1] According to Buddhaghosa the term dhammas has a generalisation so wide and loose that it ‘includes “everything” that can be known or thought of in any way,’ thus it has been rendered ‘phenomena.’ Buddhaghosa. (1991) The Path of Purification: Visuddhimagga. Buddhist Publication Society. p186.

[2] Noa Ronkin. (2005) Early Buddhist Metaphysics: the making of a philosophical tradition. RoutledgeCurzon. p44.

[3] Ibid. p38.

[4] ‘As to the eye, the organ of vision, correspond visible things (rupa,) so to the organ of the inner sense, manas, correspond non-corporeal mental things (dhamma.)’ Collected Wheel publications. Volume V, Numbers 61-75. Buddhist Publication Society, Sri Lanka. (2008) p369.

[5] Perspective: ‘seeing through’: from the Latin per-, through + specere, to look.

[6] Likewise, we might be under the impression that the person is not constituted by five impermanent and interconnected constituents (skandhas) but is fixed; or that engagement with the six bases of sense consciousness is not a potential fetter to spiritual development; or that those listed are not the factors leading to Awakening; or that the Four Noble Truths do not describe the human situation at the highest level: for example, suffering is not inherent in existence.

[7] A context reflects how a particular set of ideas, practices, institutions and associations are woven together (context; con-, together; texere. to weave).

[8] ‘(Tanha) is a notion that is best understood … as a metaphor that evokes the general condition that all unenlightened beings find themselves in in the world; a state of being characterized by a “thirst” that compels a pursuit for appeasement, the urge to seek out some form of gratification. In other words, tanha is a metaphor for the existential and affective ground underlying the whole of samsaric existence, the ground out of which spring the various strivings for satisfaction, fulfilment and meaning.’ Morrison, R. (Dharmachari Sagaramati) ‘Three Cheers for Tanha’ Western Buddhist Review. Vol. 2. 1997.

[9] Puthujjana; ‘One of the many folk’; a ‘worldling’ or run of the mill person. An ordinary person who has not yet realized any of the four stages of Awakening.

https;//www.wisdomlib.org/definition/puthujjana#buddhism

[10]‘ Prajna is present in one who “possesses wisdom directed to arising and passing away, which is noble and penetrative, leading to the complete destruction of suffering”; it is ‘seen’ in the four Noble Truths. (Samyutta Nikaya 1670-1)

Users Today : 45

Users Today : 45 Users Yesterday : 23

Users Yesterday : 23 This Month : 502

This Month : 502 Total Users : 13930

Total Users : 13930