Below is an excerpt from my forthcoming book…

© Mahabodhi Burton

7 minute read

Diving into Chapter 1, ‘The Evidence Bases of Religion, Science and Politics,’ this excerpt explores Imagination in the Coleridgeian sense and the symbol as ‘conductor’ of Reality (Capital R.) It follows on from Kindness as a common thread amongst religions.

Imagination and ‘Poetic Logic’

As religion freely applies the use of ritual and symbolism, it is important, now—in our coverage of the topic—to spend some time understanding the principles behind those; as well as introducing ourselves to the most important archetypal figures in the Buddhist pantheon.

The term Industrial Revolution characterizes the period in Britain between 1760 and 1840, in which a shift took place from an agrarian economy to an industrial one. In 1816 Coleridge published the statesman’s manual[1] in which he speaks of the industrial era as suffering from ‘a general contagion of mechanic philosophy’; it being ‘the product of an unenlivened generalizing understanding’: he felt that many people—particularly the higher classes—confused the faculty of imagination with fantasy and he wanted to correct that view: to do so he coined the term esemplastic: meaning ‘to shape into one’, to describe the creative imagination:

‘The Biographia Literaria was one of Coleridge’s main critical studies in which he discusses the elements and process of writing. In this work, Coleridge establishes a criterion for good literature, making a distinction between the imagination and “fancy”. Whereas fancy rested on the mechanical and passive operations of one’s mind to accumulate and store data, imagination held a “mysterious power” to extract “hidden ideas and meaning” from such data. Thus, Coleridge argues that good literary works employ the use of the imagination and describes its power to “shape into one” and to “convey a new sense” as esemplastic.

‘He emphasizes the necessity of creating such a term as it distinguishes the imagination as extraordinary and as “it would aid the recollection of my meaning and prevent it being confounded with the usual import of the word imagination. Use of the word has been limited to describing mental processes and writing, such as “the esemplastic power of a great mind to simplify the difficult”, or “the esemplastic power of the poetic imagination”.

‘The meaning conveyed in such a sentence is the process of someone, most likely a poet, taking images, words, and emotions from a number of realms of human endeavour and thought and unifying them all into a single work. Coleridge argues that such an accomplishment requires an enormous effort of the imagination and, therefore, should be granted with its own term.’[2]

As Kulananda says:

‘Reason and emotion come together in the imagination. ‘Imagination’ here is not the same as mere fantasy. It doesn’t stand for that which isn’t truly real. Just the opposite, in fact. To really see something–to see it in its very depths, as it really is–is to see it as marked with the characteristics of the open dimension.[3]

‘All great art shows this to some extent. Van Gogh, for example, showed in his famous painting that a chair is not just a chair. It is a luminous, transitory phenomenon, alive with the marks of human creativity, significant far beyond its mere utility.’[4]

Bearing in mind that when I speak of imagination in the following text, I mean it in this higher–esemplastic—sense; to understand the true nature of Imagination (capital I) with its benefits and drawbacks, it is helpful to review a complex symbol from Tibetan Buddhism: the Mandala of the Five Buddhas.

The Mandala of the Five Buddhas

But before we look at the Mandala of the Five Buddhas itself, we need to understand the nature of a few related concepts: the archetype; the symbol; and the mandala.

The archetype

Firstly, the archetype: we might say that an archetype represents a ‘pattern’ in the Universe, useful because it can be readily recognized ‘underneath’ or ‘within’ any concrete example; for instance, we might recognize a certain play as a ‘rags to riches story,’ comedy or tragedy. The archetype somehow ‘contains’ or ‘stands for’ the important message or ‘Reality’ that needs to be taken in.

Etymologically, the word means ‘the original pattern from which copies are made,’[5] or ‘a main model that other statements, patterns of behavior, and objects copy, emulate, or “merge” into;’[6] Sangharakshita calls it ‘the original pattern or model of a work, or model from which a thing is made or formed.’[7]

As the Platonic concept of pure form, the archetype is ‘believed to embody the fundamental characteristics of a thing;’[8] it can be ‘a collectively-inherited unconscious idea, a pattern of thought, image, etc., that is universally present, in individual psyches, as in Jungian psychology;’ or it can be ‘a constantly recurring symbol or motif in literature, painting, or mythology. This definition refers to the recurrence of characters or ideas sharing similar traits throughout various, seemingly unrelated cases in classic storytelling, media, etc.’[9]

In human psychology, ‘archetypal patterning’ is seen to exist at a pre-conscious level:

‘Archetypes are also very close analogies to instincts, in that, long before any consciousness develops, it is the impersonal and inherited traits of human beings that present and motivate human behavior. They also continue to influence feelings and behavior even after some degree of consciousness developed later on.’[10]

This is obviously the case because, if we view each archetype as related to a certain ‘reality:’ and therefore to a certain aspect of survival, such archetypal instincts would a) need to manifest early in the development of the psyche, and b) need to be reinforced throughout childhood and adult life: through exposure to story, myth, legend and culture generally.

The symbol

Closely related to the archetype is the symbol. According to Sangharakshita, ‘a symbol is generally defined as a visible sign of something invisible. Just a sign. But we may say a symbol is really, philosophically, religiously, more than that. A symbol, we may say, is something existing on a lower plane which is in correspondence with something existing on a higher plane.’[11] He cites the example of the sun being a symbol for god.

‘Just to cite a very common example, in the various theistic traditions, the sun is a symbol of god, because the sun performs in the physical universe the same function that god, according to these systems, performs in the spiritual universe. The sun sheds light, sheds heat and so on. In the same way, god, according to these systems, sheds the light of knowledge, the warmth of love and so on, in the spiritual universe. So the sun is not just a sign of god; the sun is a symbol in the sense that the sun is, on a lower level, that which god is, on a higher level. … This is of course, the old Hermetic idea of “As above, so below”.’[12]

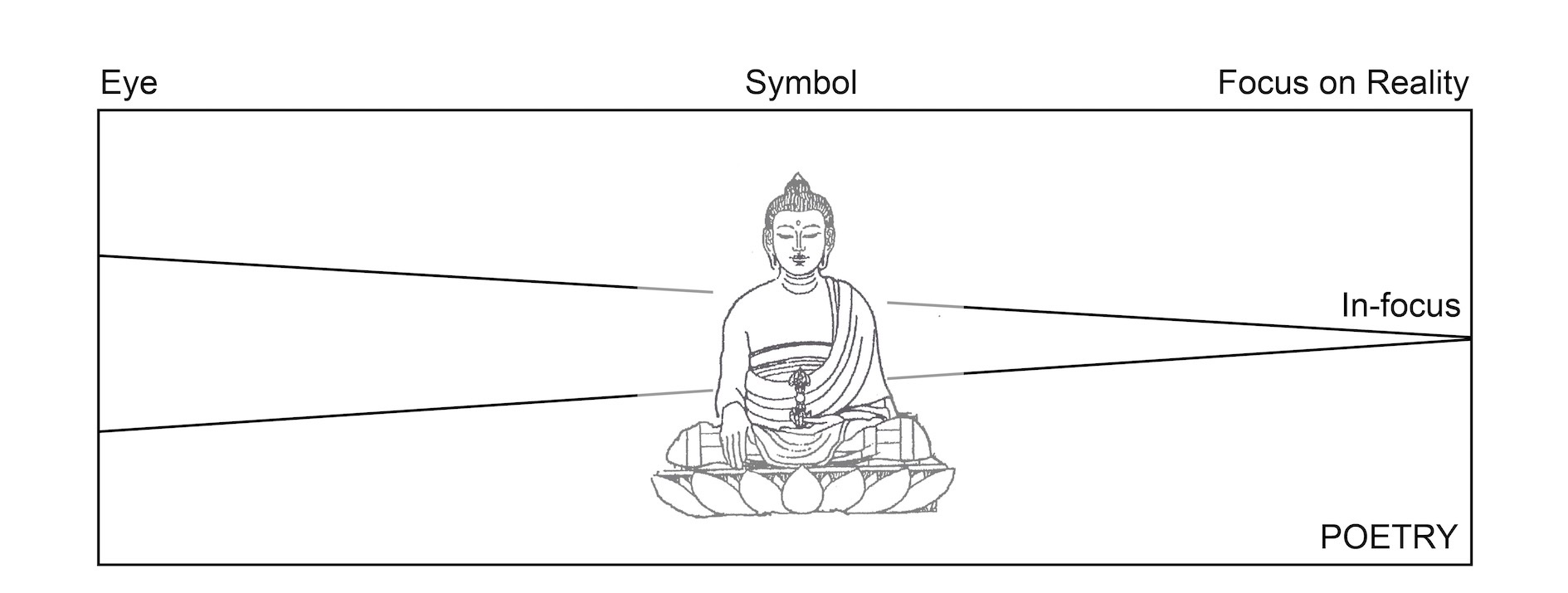

Take the Buddha image, sat in meditation posture with elongated earlobes and a protuberance on the crown of his head: it is only a symbol, not the actual reality of Enlightenment. The image can only take us part-way: we must try to see beyond the archetypal / idealized form that the symbol, and work with our imagination on it; only then will we be able to dimly glimpse what the Enlightened state might be like.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge saw symbols as ‘the living educts of the imagination … consubstantial with the truth, of which they are the conductors.’[13] Anthony Stephens sees the symbol as a ‘bridge of meaning between the known and the unknown’:

‘The strange must be ‘thrown together’ with the familiar to construct a bridge of meaning between the known and the unknown.’[14]

Or, as Douglas Hedley puts it:

‘A symbol is quite literally that which is a sym-ballein, which is a throwing together. What does the symbol throw together: the eternal and the temporal, the transcendent and the immanent? It is through the symbol that our awareness of the transcendent is made conscious. It opens up a path to that transcendent realm.

‘The symbol, as Coleridge says, partakes in that which it is symbolizing. So, a beautiful object, which is symbolizing the holy, is itself—although it is not the holy, the transcendent—it is participating in it.’ [15]

COLERIDGE & ROMANTICISM BY DOUGLAS HEDLEY

The problem the symbol solves is that realities such as God, Enlightenment and Reality (capital R) are ineffable: our minds without help are unable to encompass them. Symbolism evolved because of humankind’s need to come into relationship with that which is above, unknown, beyond control, yet somehow useful to acknowledge. Humans may have made fire by abstracting the concept of ‘heat’ from diverse aspects of experience and using intelligence to create the technology ‘fire’, but they also drew out from the fabric of the Universe moral patterns such as ‘justice’ and ‘the good,’ which could not be made into concrete objects, but as patterns in the Universe they could be honoured and respected through an appropriate symbol (‘The scales of justice’) or archetype (‘God’’) and remembered in ritual and devotional practice.

‘Soft-focus’ version of reality

It might be helpful to view the symbol as a ‘soft-focus version’ of the reality that it represents (see diagram,) rather than its hard literal expression. If we can maintain a sense of the symbol as ‘play object’ or ‘pretend version of reality’ through the suspension of disbelief,[16] then we gain access to that reality; something of the reality ‘passes through’ the symbol to us. Seeing the symbol for what it is, and conscious of those elements that are artifice, we are able ‘look through’ the symbol and thus focus on the truth.

The moral message that a myth or story wishes the reader to absorb will often be combined with fantastical elements requiring suspension of disbelief or be stylized in some way which softens the message and makes it palatable. Those elements of fantasy, artifice, pretence and idealisation effectively create in the myth a kind of ‘soft-focus’ version of the truth of which the myth is ‘the conductor.’ This palatability allows stories, myths and symbols to gain in meaning and positive association over time, eventually becoming central within a persons’ life. Without such ‘idealization’–what we might call ’aesthetic cushioning,’ the truth is quite likely to ‘bounce off.’

Having claimed that each symbol is a conduit to a certain truth or reality, we need to bear in mind that ‘truth claims’ are made by all religious adherents: the symbol just represents the truth for the person adopting and relating to it: whether it is the truth in actuality will depend on how the Universe ‘answers back’ when we use it.

The chapter continues by exploring the idea of the mandala.

[1] Full title: The statesman’s manual: or, The Bible the best guide to political skill and foresight: a lay sermon, addressed to the higher classes of society, with an appendix, containing comments and essays connected with the study of the inspired writings. The full text is available on the Internet Archive at:

https://archive.org/details/statesmansmanual00coleuoft/page/n3/mode/2up?ref=ol&view=theater

[2] ‘Esemplastic.’ Art and Popular Culture.

http://www.artandpopularculture.com/Esemplastic Retrieved 9 August 2022.

[3] The ‘open dimension of being’ is a term used in Triratna to indicate a state of creative potentiality, in which ‘anything can happen.’ See later in chapter.

[4] Kulananda. (1997) Western Buddhism. Thorsons. p125.

[5] ‘[It] derives from the … Greek noun archétypon, whose adjective form is archétypos, which means “first-molded”, which is a compound of arch?, “beginning, origin”, and týpos, which can mean, amongst other things, “pattern”, “model”, or “type”. It, thus, referred to the beginning or origin of the pattern, model or type.’ Archetype.’ Wikipedia. Accessed 17 December 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archetype

[6] ‘Archetype.’ Wikipedia.

[7] Sangharakshita. Archetypal Symbolism in the Biography of the Buddha. Free Buddhist Audio. https://www.freebuddhistaudio.com/texts/read?at=text&num=043

[8] ‘Archetype.’ Wikipedia.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Sangharakshita. Archetypal Symbolism in the Biography of the Buddha.

[12] Ibid.

[13] ‘In the scriptures they are the living educts of the imagination and of that reconciling and mediatory power, which incorporating the reason in images of the sense, and organizing (as it were) the flux of the senses by the permanence and self-circling energies of the reason, gives birth to a system of symbols harmonious in themselves and consubstantial with the truth, of which they are the conductors.’ Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The Statesman’s Manual. See ‘Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Romanticism’ by Douglas Hedley. Timeline Theological Videos. YouTube. 8 February 1013.

https://youtu.be/GzyI6B745BI The above quote is taken from the full video of 25 minutes which is available on the St John’s Timeline YouTube channel.

https://www.youtube.com/user/StJohnsNottingham/search?query=hedley

[14] Anthony Stevens. (2001) Ariadne’s Clue: A Guide to the Symbols of Humankind, Princeton University Press. p13.

[15] ‘Coleridge and Romanticism by Douglas Hedley.’ Timeline Theological Videos. YouTube. 8 February 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GzyI6B745BI&t=11s

[16] Phrase coined by Coleridge.

Users Today : 18

Users Today : 18 Users Yesterday : 23

Users Yesterday : 23 This Month : 476

This Month : 476 Total Users : 13903

Total Users : 13903