Below is an excerpt from my forthcoming book…

© Mahabodhi Burton

12 minute read

This excerpt is taken from the chapter on ‘The Evidence Bases in Religion, Science and Politics.’ It follows on from the section on ‘Tantric Deities’ and explores ‘Functional Imagination.’

The five wisdoms (jnanas)

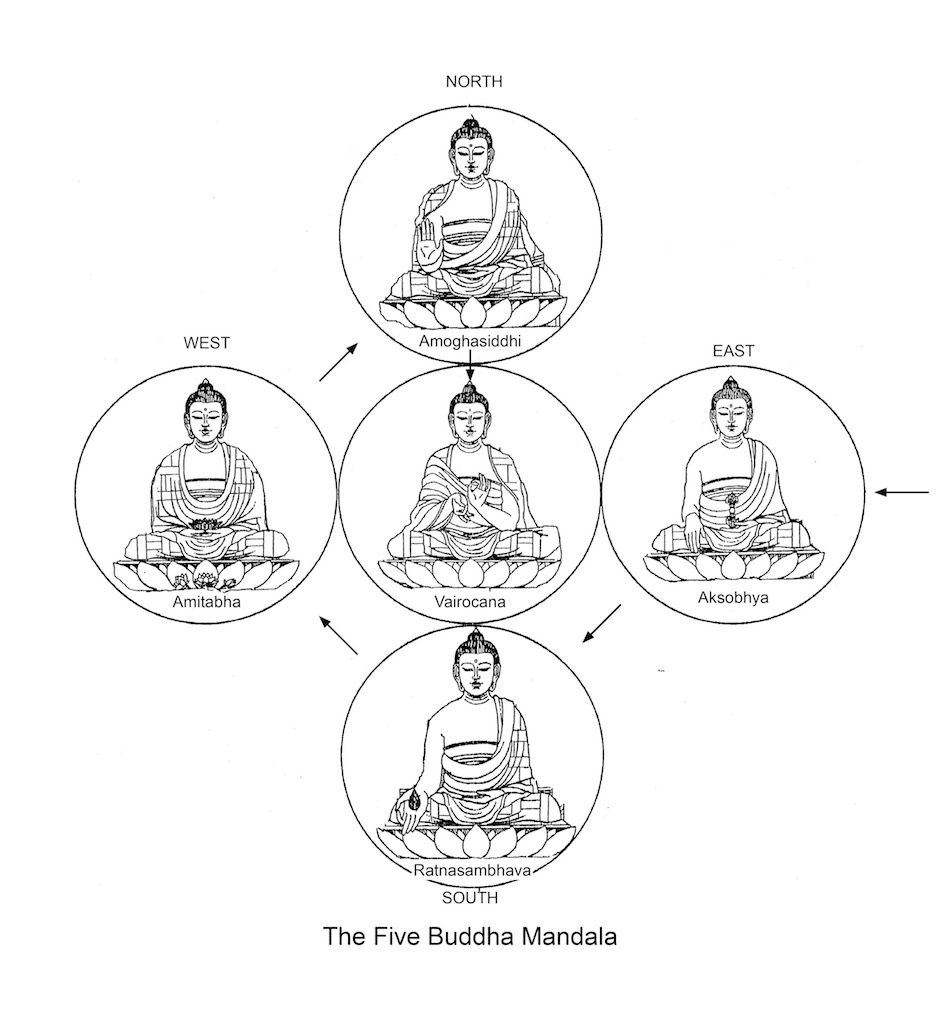

The Mandala of the Five Buddhas expresses the fact that a whole range of often complementary qualities are present in the Enlightenment experience. Whatever is at the centre of a mandala orders the mandala: as the king his kingdom. Each Buddha has a specific wisdom: Vairocana’s Supreme Wisdom could be said to be the combined effect of the other four:

- Aksobhya: Mirror-like Wisdom

- Ratnasambhava: Wisdom of Equality

- Amitabha: Discriminating Wisdom

- Amoghasiddhi: Action-Accomplishing Wisdom

We will see how these wisdoms can be brought to bear on current world problems at the ends of Chapters 2 to 6.

Poetic logic

In Tibetan ritual practice one enters the mandala from the east; then proceeds to the south, the west, the north and finally moves into the centre. This sequence, combined with the symbolism and associations of the Five Buddhas, illustrates the process in operation when we are dealing with the field of Imagination: which includes symbolism, myth; and therefore religion.

Imagination and symbolism may be the only way we have to engage our emotions with those patterns in the universe that we wish to respect and remember. And like concepts, they have an inner logic, which I choose to call ‘poetic logic.’

There are five elements to poetic logic:

- The way that we view imagination, poetry and symbolism

- The quality of the symbol in representing Right View

- The degree to which we believe in / dwell upon the symbol

- The actions we take in relation to it

- The degree to which we are transformed by it, and into what

Or, in one word; 1) Reason, 2) Beauty (the object itself), 3) Emotion, 4) Action (the action in relation to it), 5) The Change brought about; Imagination engages all of our faculties in order to bring about change.

However, it cuts both ways; Imagination can lead to growth, but it can equally lead to delusion. The former I call Functional Imagination, the latter Dysfunctional Imagination.

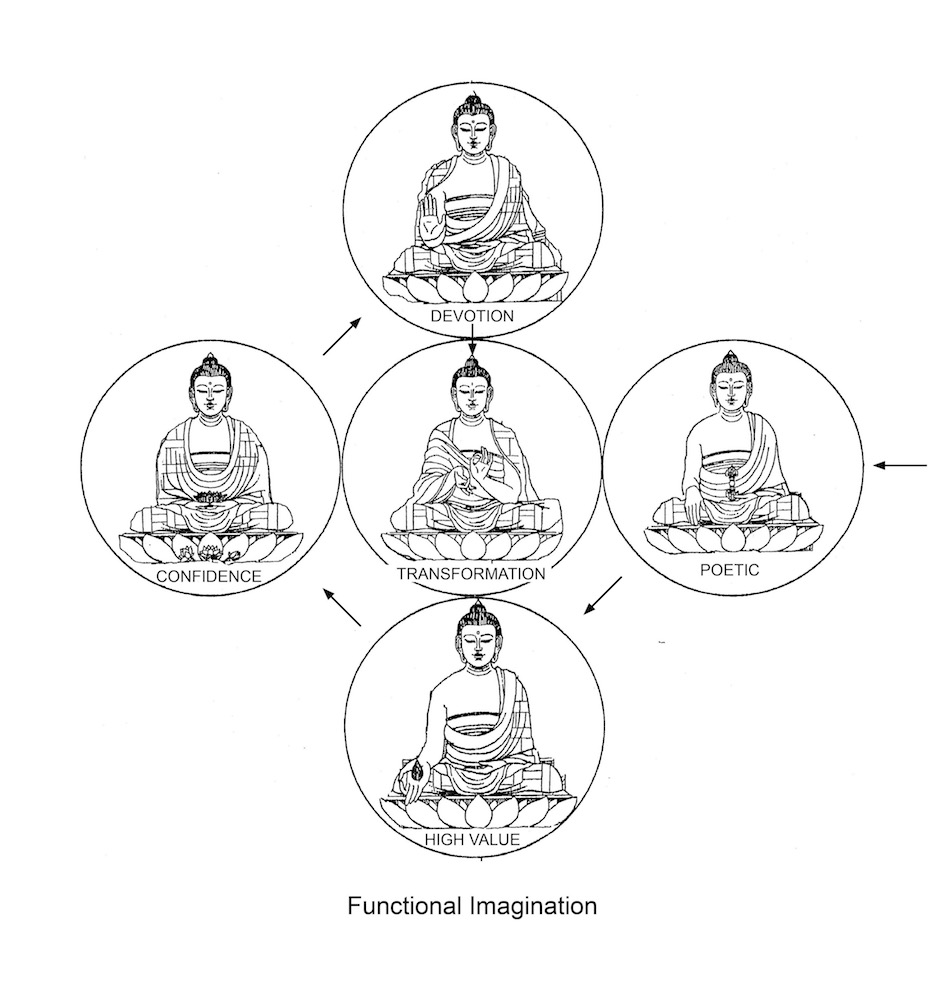

Functional Imagination

The first sequence—called ‘Functional Imagination’—illustrates how a person engages creatively with symbols to bring about personal growth and transformation. By taking symbols poetically; by engaging with ones of high intrinsic value; by repeatedly dwelling on them with confidence (perhaps acting ‘as if’ they are true: suspending disbelief and stepping into them as if they are the reality); and by practicing rituals / devotion towards them, the devotee will be positively transformed by the experience and will move closer to the reality that the symbol represents.

See as poetry

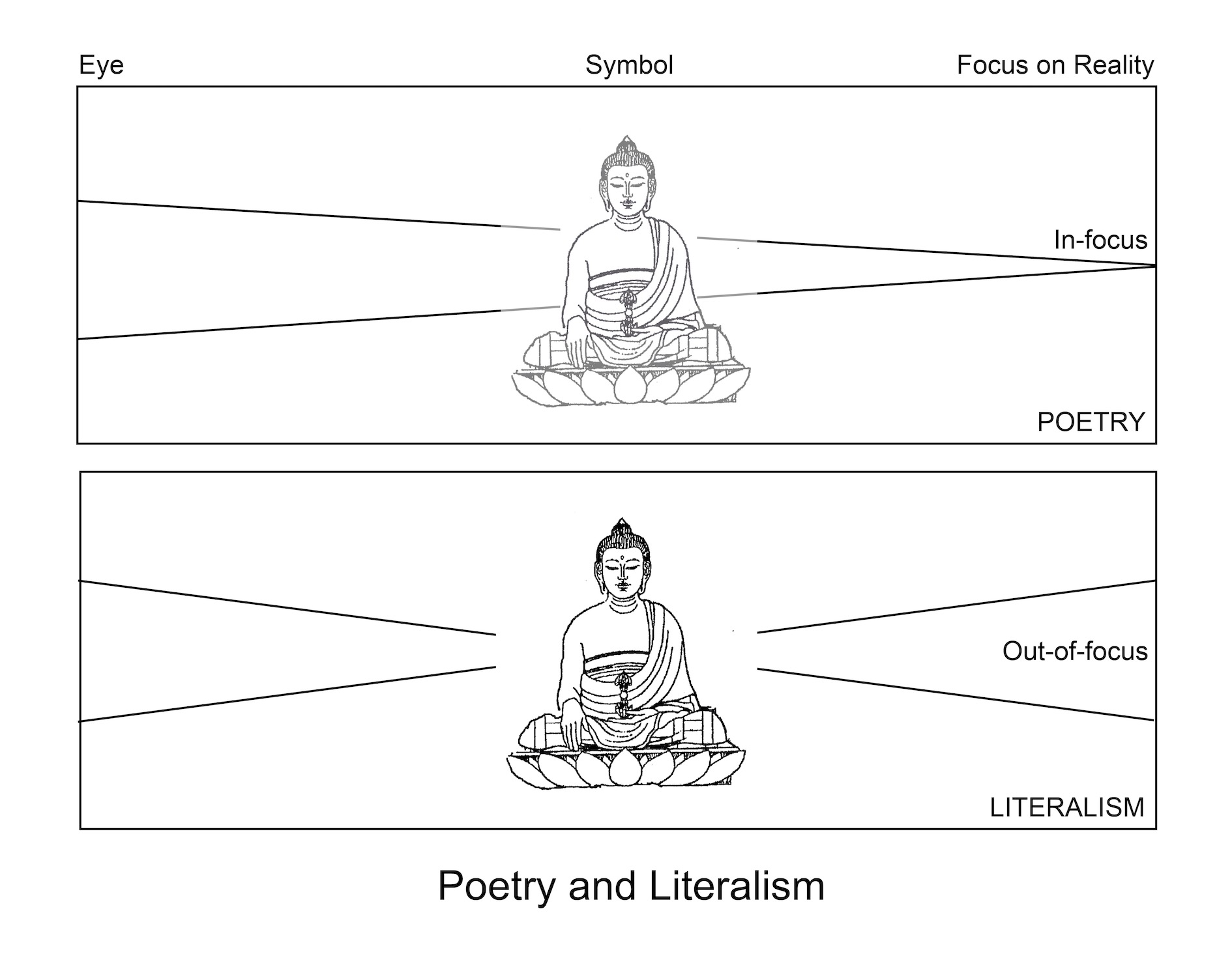

The first thing we need to be sure of when we are dealing with symbols and myths is that we need to see them as such; we need to see the poetic as poetic, the imaginative as imaginative, as reflected in the hand gesture of the dark blue Buddha Aksobhya, who touches the earth: recognizing just what the poetic is and isn’t. We need to see that symbols are a means to grope towards an aspect of reality that is essentially ungraspable; it is beyond description and can only be accessed through the prism of the symbol.

Literalism

On the other hand, if we don’t see symbols and myths for what they are—a means to grope towards a greater reality; if we view a symbol unwisely, and take it literally, then the reality that it represents is out-of-focus, and the whole meaning behind having the symbol in the first place is broken.

If you find yourself reacting to ‘unreasonable aspects’ of a story, try letting those details drift ‘out-of-focus’; try to treat them more lightly, and see what is different in what comes through to you; look for the ’general shape and impact’ of the story, rather than focusing on the particulars, and that will probably be a more satisfying experience, if the story’s message is worthwhile. I think that this is why—without a sense of the reality that ritual is attempting to approach, it will always appear as ‘mumbo-jumbo’ to the outsider: this is why ritual can never be a performance; it is meaningless unless its participants are open to connecting with the significance that the object of ritual represents.

Of high intrinsic value

The second thing we need to be sure of when we are dealing with symbols and myths is that we need to choose symbols to relate to which have the highest intrinsic value, as mirrored by the symbol associated with yellow Buddha Ratnasambhava: the jewel. We need to isolate and treat as precious that which is most sublime: in the sense of being most true—representing Right View, but also of the greatest beauty,[1] thus, engaging the emotions.

We also need to develop awareness refined enough to be able to appreciate it. In his chapter ‘Nature and Art’ from Life with Full Attention, Maitreyabandhu reviews Elizabeth Bishop’s poem Sandpiper and the transformative power of appreciation:

‘The spiritual value of the appreciative mode is in its non-utilitarian, non-acquisitive nature. Appreciation is an end in itself. It is its own reward. And as we develop this appreciative mode, we start to become sensitized to how so much of modern life is ugly. We notice how banal the media can be, how unpalatable harsh speech, cynical ideas, and snide remarks are. We start to notice that egotism, in all of its myriad guises, is not very productive—we see how uncreative it is, how coarse and predictable. True appreciation is a letting-go of self, a letting-go of egotism. When we are absorbed in the appreciative awareness of a tree, or a poem, or a sandpiper, we forget ourselves and, by doing so, we transcend ourselves. Or to put it another way: in our moments of deep appreciation, self becomes relational. Instead of tending to be entrenched, repetitive, and habitual, self becomes open-ended, spontaneous, and creative. In Elizabeth Bishop’s Sandpiper’, self and world modify and animate one another.’[2]

Our symbol needs to express a Right View in the most emotionally engaging way possible. Great art and literature do this—for instance, Michaelangelo’s Sistine Chapel conveys certain truths about the human condition in a way that is uplifting and inspiring, but which also challenges the viewer. Within Buddhist literature, Shantideva’s Bodhicaryavatara expresses the lofty altruistic sentiments to be expected of a true individual far along the Buddhist path—those held in the elevated mindset of the Bodhisattva: the Ideal Buddhist of Mahayana Buddhism, as follows:

Shantideva is being poetic and so we don’t have to take his words literally, although—as we will see in the next section, there can be value in ‘acting as if’ we take the verses literally: collectively reciting the verses in a devotional ceremony, we can pretend that we are advanced Bodhisattvas for whom the sentiments expressed would be true, and this can help those sentiments go in more deeply for us.

For Coleridge the ideal poet ‘brings the whole soul of man into activity.’ Coleridge defines imagination as the esemplastic power; having the power to unify; to mould into one. What they create has the emotional power to transform their audience. The way that words themselves are savoured, repeated, played with, and juxtaposed paints a picture that places that information in the human context, accounting for the fact that humans cannot hear potentially challenging information only once or twice and accept it; they must hear it again and again, and in delightful ways, to absorb and accept it. The visual arts too employ gesture in a similar way through line, texture, and form. For this reason, religious devotion is shot through with colour, mystery, and repetition, using chant, mantra, and incantation to get its message across.

The subject of poetry is often the realities of life and death, of loss and love, where the gestural quality of its language softens the message, allowing for what W.B. Yeats called ‘truth seen with passion.’ When speech loses all gesture communication becomes a series of instructions; it becomes rhetorical in a corrupt sense—as in Orwellian double-speak, designed to beguile its audience, and mould their opinions. For Jeffrey Wainwright language is inevitably poetic in its gestural qualities, but it comes to the fore in ceremony when the ‘right words’ are required, in ‘heightened deliberate speech.’ [3]

‘Poetry can be seen as a particular space, created or adapted by the poet out of the flux of language-use with great deliberation.’[4]

Thus, it was Coleridge’s view that the poet’s creativity required monumental effort; part of their skill being directed at creating a reflective / sacred space:

‘A poem is part of the functioning and the gesturing of the words we use every day, but it is also set aside. Just as a prayer mat is made of fabric found everywhere but once laid out, marks off a space from the surrounding daily world, so does the shape of a poem organize language into a space for pause and for different attention.’[5]

Having confidence in

The third thing we need to be sure of when we are dealing with symbols and myths is that we need to give them our attention. Moving to the west we meet Amitabha, who is associated with meditation and with the faith schools of Japanese Buddhism (Jodo Shinshu); his symbol is the lotus flower; symbolizing personal growth and unfolding potential.

A symbol of high value will be of no use unless we regularly reflect on it: unless we meditate upon it; a myth of high value will be of no use unless we live it. This is the thing we need to do next for our imagination to come alive.

To meditate is to take a quality that we want to develop, such as loving kindness; choose that quality over others; and keep coming back to whether we are developing it or not: this is how loving kindness will grow within us. Likewise, repeatedly giving a symbol or myth our attention helps it grow within us and inform our lives. It is to this end that religious devotees build temples; stay in ashrams, dress in costumes, and practise devotion: the temple marks out a sacred space within which to strengthen one’s confidence in the values held sacred.

One of the Buddha’s disciples most associated with faith is the old monk Pinghiya:[6] having praised the Buddha thoroughly, he is asked why he dwells apart from him, even for a moment. Pinghiya replies that there is never any time that he is not present with the Buddha:

‘Heedful, O Brahmin, night and day,

I see him with my mind as if with my eyes.

I pass the night paying homage to him;

Hence, I do not think I am apart from him.

‘My faith and rapture, mind and mindfulness,

Do not depart from Gotama’s teaching.

To whatever direction the one of broad wisdom goes,

I pay homage to him in that same direction.

‘Since I am old and feeble,

My body does not travel there,

But I go constantly on a journey of thought,

For my mind, Brahmin, is united with him.’[7]

Pure Land Buddhism is similarly faith-based: its followers believe that if a person has enough faith as they chant the Nembutsu; ‘Homage to Amida Buddha’[8], they will be guaranteed to be reborn in the pure land Sukhavati,[9] a kind of Buddhist paradise, in which the trees are made from the seven precious substances; the birds sing the Dharma; ones wish comes true as soon as one thinks of it; there is no suffering and one hears the Dharma at will. Both are examples of how faith builds an emotional connection with the Ideal. There are many pure lands, associated with different archetypal Buddhas: the important thing about them being that they are the ideal places from which to attain Enlightenment: in fact, once one resides there, the conditions are so strong that Enlightenment is guaranteed.

Expressing devotion towards

The fourth thing we need to be sure of when we are dealing with symbols and myths is that we need to perform devotion in relation to those symbols. Proceeding around the mandala to the north we meet Amoghasiddhi: associated with successful action and fearlessness, he is always successful in everything he does.

A ritual is a symbolic action that ’mirrors’ an intentional action in the world; when a couple intends to spend their lives together, they have the choice to symbolically mark that intention with a marriage ceremony; or, when a family intends to honour their connection with a deceased family member, they will usually mark that intention with a funeral and perhaps a wake: the memory of the ceremony and the sentiments expressed within it will later remind the celebrants of those intentions.

Life is full of ritual. When we proffer a handshake, we make a symbolic gesture: the ‘gift’ of our hand is symbolic of cooperation—it was originally meant to reveal that we had no weapon: by offering our hand or accepting another’s we symbolically are indicating our desire to collaborate: something along the lines of: ‘I will support you in your endeavours, in whatever way I can, as I trust you will with mine.’

Amoghasiddhi represents successfully bringing our values into the world and expressing them visibly. It is all too easy for us to build up a clarity of vision accompanied by compassionate mental states in the privacy of our meditation practice or retreat, but then for that clarity and positivity to quickly evaporate when we become exposed to the hurly-burly of the world. The Greek god Hermes—or the Roman god Mercury—was called the ‘messenger of the Gods.’ In Buddhism, a God-like state is an analogy for a creative mental state: so, Hermes represents an ability to bring creative states into the world, without them being besmirched; the analogy suggests a mercurial quick-wittedness being required for the task.

When we have values that we are not sure others share, this can be a cause for concern; will we be mocked or even attacked for our views; our culture; our values? Hence the association of the dark green Buddha with fearlessness—he holds his right hand in front of his chest, palm facing outwards, in what is called the abhaya mudra: the gesture of fearlessness.

The way that we connect with our values through action is by performing ritual: an example I often give of a Buddhist ritual is a simple one we performed when my work colleague left for a new job. John was a co-worker in Earth Cafe, in the basement of the Buddhist Centre. The team sat in a circle around a Buddhist shrine; firstly, we took it in turns to rejoice in his good qualities; then John said something of his own; and then, after we began chanting a mantra—which acknowledged our shared Buddhist context with him—at an appropriate point John stood, bowed to the Buddha, and left the room; that was the ritual. After John left, I had the definite feeling that he had now left the cafe team: the ritual had ‘helped the penny drop.’

Important rituals in life often involve an ordeal, which is designed to make the experience—or more importantly—what the ritual signifies, unforgettable: for instance, when a young man in Africa is initiated into manhood he is often scarred on his cheek: which is the outward sign of him now being a man; a Zen Buddhist postulant may kneel in the snow outside the monastery for several days as a sign of their resolve, before they are allowed inside; my path to being ordained into the Triratna Order held something of an ordeal; seven years of preparation, assessment and anxious waiting flushed out my distorted motivation: when I did eventually join the Order it really meant something. During the ordination ceremony I took four vows which voiced my commitment:

With loyalty to my teachers, I accept this ordination.

In harmony with friends and brethren, I accept this ordination.

For the attainment of Enlightenment, I accept this ordination.

For the benefit of all beings, I accept this ordination.

Devotion plays an important part in keeping what we value in view, in fact, the word itself derived from ‘vow’: a bond or a promise; devotion then involves keeping a promise to ourselves to remember what is valuable to us: it involves mindfulness of value. Whenever we perform devotion towards a religious icon; bow; pray; recite verses; chant mantras or sing hymns we strengthen our bond with the object of our devotion. Ritual and devotion at its most pure are the confident performance of ritual and heartfelt devotion to Buddhist ideals of the high-ranking Tibetan Lama: practising devotion over many years they have made those Ideals strong within themselves.

The power of ritual is in the fact that it is an overt expression: even if you are practicing on your own—with no-one watching—you know that you have done it. However, most ritual and devotion are practised collectively: this cements the community in its beliefs and helps the individual be more conscious of their own values. Religious commitment and devotion are essentially a matter for the individual: this is why ritual can never be a performance; performance involves an audience, who may or may not be committed to the values that are acknowledged in the ritual.

It is because we intend to live in particular ways—i.e., we choose to live out a particular religious or secular life—that we are attached to our symbols and rituals: therefore, emotional investment in icons can lead to explosive clashes between religions and cultures. Quite apart from the significant loss of life, the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Centre and Pentagon stunned Americans because a key symbol was attacked; similarly, when in 1984 the Indian army—seeking to arrest Sikh militants—attacked the holy Golden temple at Amritsar Sikhs worldwide interpreted it as an attack on the Sikh religion, which led to the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards, followed by further Sikh deaths in anti-Sikh riots.

Being helpfully transformed by

The final thing we need to be sure of when we are dealing with symbols and myths is that we combine all of these qualities together: we take symbols poetically; we choose this of the highest value; we meditate upon those symbols; we live out those myths; and finally, we demonstrate our commitment to them—to ourselves and others—by practicing devotion in relation to them; we make them a key part of our active life. If we do all these things then we are sure to be transformed by the power of our Imagination, moving inexorably towards embodying our Ideals.

But this won’t be easy: faith in Buddhism is based on a combination of reason, intuition and experience, and Imagination must marshal all these too, if it is to succeed. To create something new, whether in the Arts, Sciences, Humanities or Religion—a new art movement: a new scientific insight; a new religious movement—is a task, according to Coleridge, that requires monumental effort, discipline, and training.

This is no doubt why Vairocana—who is associated with teaching, but really with transformation—is depicted seated on a lotus throne with lions at his feet, and he is said to ‘roar the lion’s roar’ of the Dharma. His colour is pure white, a colour always associated with reality with a capital R: this is the place we are moving towards through our practise of Functional Imagination.

The chapter goes on to explore ‘Dysfunctional Imagination.’

[1] See Subhuti. ‘The Ascent of Beauty.’ Apramada. 4 May 2022.

https://apramada.org/articles/the-ascent-of-beauty

[2] Maitreyabandhu. (2009) Life with Full Attention. Windhorse. p193.

[3] Wainwright, J. (2015) Poetry; the Basics. Routledge. p5.

[4] Ibid. p9.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Priyavadita. ‘Me and My Mate Pinghiya.’ Audio talk. Manchester Buddhist Centre. 22 January 2018.

https://manchesterbuddhistcentre.org.uk/meandmymatepingya/

[7] Bhikkhu Bodhi (translated from the Pali). The Suttanipata: An Ancient Collection of the Buddha’s Discourses Together with Its Commentaries. Wisdom. p347.

[8] Amida is another name for Amitabha.

[9] Sukhavati means ‘Happy Land.’

Users Today : 120

Users Today : 120 Users Yesterday : 23

Users Yesterday : 23 This Month : 578

This Month : 578 Total Users : 14005

Total Users : 14005