Below is an excerpt from my forthcoming book…

© Mahabodhi Burton

5 minute read

This excerpt is taken from the chapter on ‘Buddhist Practice and follows on from the section on ‘Imagination.’

Ritual and devotion

Ritual and devotion is an important aspect of Buddhist practice, which most Buddhists engage in, to some degree—although admittedly some people are more temperamentally averse to it than others.[1] Some of that resistance may be due to the person questioning the value of imagination per se—as in seeing imagination as fantasy, and therefore as a form of delusion—but this is a wrong view: when imagination takes us into a world of unreality—then it is fantasy, but when it brings us closer to reality—then it is Imagination proper. Generally, ritual and devotion are a way of building confidence in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha; through bringing them to mind and engaging with them emotionally—even physically—as when we make offerings to, or bow to, a Buddhist shrine.

Image of Wat Phra Dhammakaya in Pathum Thani, Thailand by suc on Pixabay.

Image of Wat Phra Dhammakaya in Pathum Thani, Thailand by suc on Pixabay.

Confidence

Shraddha means “to place one’s heart upon” and represents an emotional interest in Buddhist practice and the confidence that such practice will bring ourselves and others the happiness that we desire; to the extent that faith (in Buddhism) is present, a person’s attention, thought and emotion—that is, the whole of their citta—is oriented towards its object. This idea is reflected in the fact that there are three grounds for confidence in Buddhism—reason, intuition and experience. Unlike its equivalent in theistic religion, faith in Buddhism is never blind. And just as reflection practices are designed to cultivate wisdom, by guiding the intellect towards Right View, devotional practices are designed to cultivate confidence, by guiding our emotions towards the Buddhist Ideal.

What we value we adorn! The design of the Apple iPhone ‘adorns’ the view that ‘technology will solve all our problems.’ Buddhist devotional practices such as offering a stick of incense, bowing to a shrine or performing a devotional ceremony (called a puja) similarly adorn an idea—but a very different one, that the practise of Buddhism will satisfy our deepest needs. They thus help solidify our emotional connection with it.

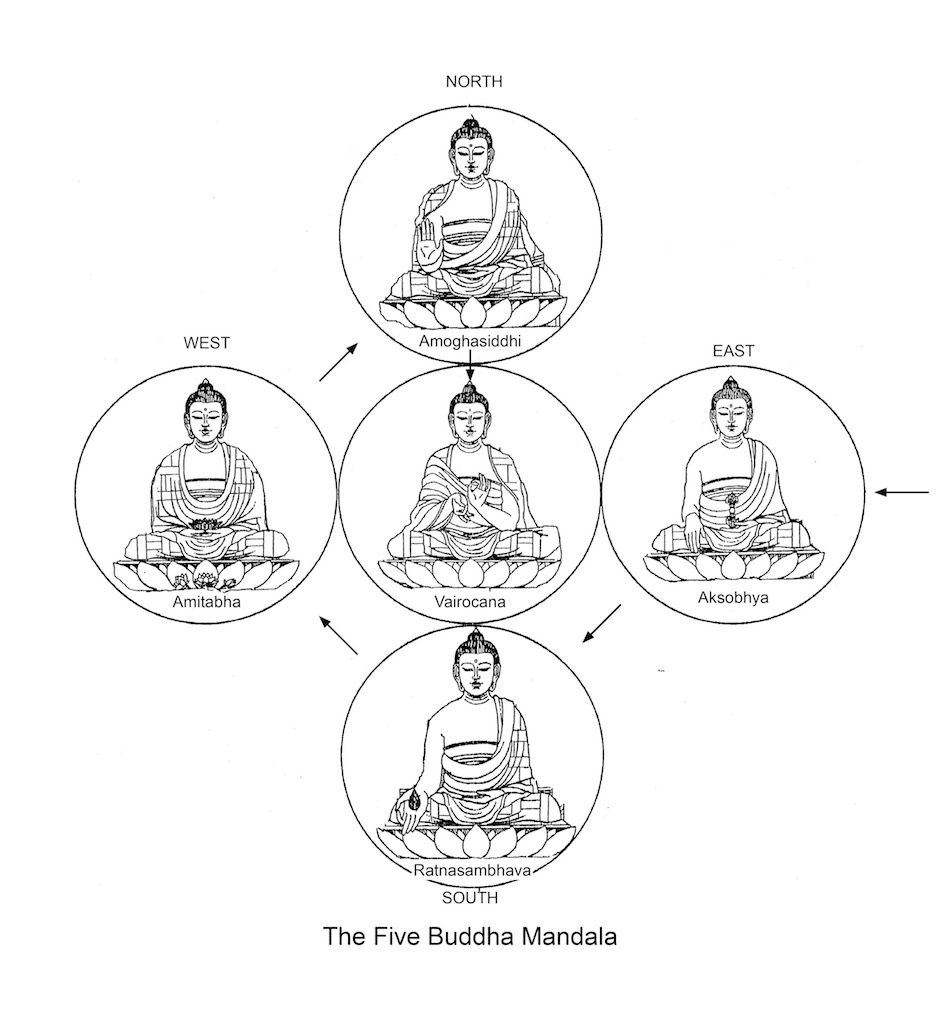

Reviewing what we explored in Chapter 1: the Buddha Aksobhya represents Non-Literalism—seeing poetry or symbolism as such; the Buddha Ratnasambhava represents the Quality of Refuge—taking up the highest value object of devotion; the Buddha Amitabha represents Non-Skepticism—acting ‘as if’ a story is true if to do so is helpful or effective; the Buddha Amoghasiddhi represents Effective Ritual Action—acting ritually in a way that fortifies devotion to a particular Ideal; and the Buddha Vairocana represents Effective Transformation—transforming the individual through the effective application of Imagination.

Each of the Buddhas in the Mandala of the Five Buddhas represents an aspect of the Enlightenment experience; and in the Tibetan pantheon there exist many other archetypal forms—including Bodhisattvas—who belong to these five families and who thus represent specific Enlightened qualities—for instance: Manjusri—the Bodhisattva of Wisdom; Avalokitesvara—the Bodhisattva of Compassion and Vajrapani—the manifestation of Enlightened Spiritual Energy.

Chanting

Each Enlightened figure has its own visual symbolism—sometimes with variations in form—and a sound symbol—also with variations—called a mantra. For instance, Avalokiteshvara’s mantra is ‘Om Mani Padme Hum’; we see the famous six syllables of this mantra carved into rock and painted in Tibetan script all over Tibet. Groups of Buddhist practitioners will chant this and other mantras—as a way of collectively remembering their commitment to the Ideal of Universal Compassion, and to bond around it as a community—perhaps before they meditate together, the advantage of chanting being, it allows for the expression of a collective commitment.

Image of Wat Phra Dhammakaya in Pathum Thani, Thailand by suc on Pixabay.

Image of Wat Phra Dhammakaya in Pathum Thani, Thailand by suc on Pixabay.

Bowing

Another common ritual practice is to bow—or make an offering to a shrine or other object of value. The problem with this kind of practice is that—growing up in a Western cultural context, people are often suspicious of acknowledging others in this way, because they feel that they are ‘giving their power away.’ However, we can understand the bow or offering in a way that is more acceptable to our rational mind.

And that is, that through bowing we are consciously allowing ourselves to be influenced by another person—or archetypal figure—whom we wish to learn from.

To bring our rational mind along, it is helpful to break the bow down into a number of logical steps – which I jokingly call the ‘Twelve Step Bowing Programme.’ Standing in front of an image of the Buddha—or someone you really admire, it might be Martin Luther King—or even a real person, and go through the following logical sequence;

| Step one | Pick a quality that you would like to develop, e.g. kindness. Reflect that it is very unlikely that you are the kindest / wisest / calmest (insert quality) being in the universe |

| Step two | Therefore, another being must be. |

| Step three | Let the person you are bowing to represent that being. |

| Step four | Be aware of the respective heights of your head; and the head of the other person. Allow your respective head heights to symbolize the person most developed in kindness. |

| Step five | Mentally acknowledge the other’s greater kindness. |

| Step six | Feel that you need to acknowledge the other’s greater kindness with an action. Symbolically lower your head so that it is below the head of the other—i.e. bow, while being conscious that the other person is kinder than you are. |

| Step seven | Consider how it would feel to be as kind as they are. |

| Step eight | Consider that the best way to become as kind as they are is to allow yourself come under their influence. |

| Step nine | Resolve to be open to their influence in this area. |

| Step ten | Kindness comes to be more on your agenda. |

| Step eleven | You become kinder. |

| Step twelve | You become as kind as they are. |

Making an Offering

People will often offer incense, lighted nightlights and flowers to a Buddhist shrine. Again, we can give our rational mind a way of being happier with what we are doing when we make an offering. If we think about it, what are we doing when we make an offering? We are bringing two things into proximity with each other: say a statue of the Buddha and a flower. The flower is symbolic. In bringing the flower into close contact with the Buddha we are saying, ’In some way, you are like this flower.’ Or if we are offering poetic verse, it is like we are saying ‘In some way, you are like these wonderful evocative experiences expressed in the verse.’ We are building up—in our conception of what the Buddha is—a bank of positive associations: that our emotions will be drawn to engage with.

Festival shrine at Manchester Buddhist Centre circa 2016. Design by Mahabodhi.

Festival shrine at Manchester Buddhist Centre circa 2016. Design by Mahabodhi.

Puja

Groups of Buddhists also get together and practise devotional ceremonies called puja. The Sanskrit word puja literally means ‘worship’: a word which—stripped of its theistic connotations—simply implies valuing (worth-ship) and within the puja both chanting and bowing / making offerings are usually incorporated.

The standard devotional text within Triratna is called the Sevenfold Puja; according to Sangharakshita the puja is sevenfold because it expresses seven moods. I would express things slightly differently, and again—giving the logical mind something to hang its devotion on—I have come up with a logical structure to the puja—consisting of seven sections, in which the desired effect of completing each stage is highlighted in black. The puja takes place in call-and-response, and the text can be viewed below. The whole sequence can be viewed as a drama, mirroring the way that transformation actually happens through practice. And it can be helpful for the participants to engage in a certain amount of play: in order to be more ‘in line’ with the sublimity of the text that they are reciting, they might ‘act as if’ they are advanced Bodhisattvas, for whom the words recited would indeed be true:

1) Worship—By reciting verses evoking exotic offerings to the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas we bring the Transcendental into the space

2) Salutation—We imagine making multiple prostrations to our objects of devotion (including the opportunity to make physical offerings, while chanting a mantra (often the Avalokiteshvara mantra) we acknowledge our desire to learn

3) Going for Refuge—We express our commitment to practicing the Buddhist Path—to the extent that we do—and to practise the ethical precepts which constitute that path we make a commitment to practice

4) Confession of Faults—We verbally acknowledge it when we have ‘fallen down’ in that commitment, resolving to remedy those faults we practise in a real way

5) Rejoicing in Merits—We express our appreciation at all the skilful actions that living beings have performed, thus creating a better world we acknowledge there are fruits to practice

6) Entreaty and Supplication—We entreat the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas to stay around to guide living beings on the path we acknowledge that we lack wisdom

**After the sixth section there is normally a ‘wisdom reading’, expressing Enlightened Wisdom we hear the dharma

**This is followed by a collective recitation of the Heart Sutra; a poetic invocation of that wisdom we ‘play’ at embodying wisdom

7) Transference of Merits—We commit ourselves to dedicate whatever wisdom we have accrued to helping others we ‘play’ at embodying compassion

**After which follows the communal chanting of the Padmasambhava mantra we acknowledge the ‘guru principle’

**When the mantra dies away, it is followed by eight concluding mantras—representing eight archetypal Buddhas and Bodhisattvas—recited three times each, in call and response we ‘play’ at being an Enlightened community

The chapter goes on to explore the Going For Refuge and Prostration Practice.

[1] Among his disciples the Buddha identified various personality types; among them the ‘doctrine follower’, who is temperamentally attracted to the rational teachings; and the ‘faith follower’, who is attracted to the more emotionally oriented practices like ritual and devotion.

Users Today : 94

Users Today : 94 Users Yesterday : 23

Users Yesterday : 23 This Month : 552

This Month : 552 Total Users : 13979

Total Users : 13979