Below is an excerpt from my forthcoming book…

© Mahabodhi Burton

6 minute read

This excerpt is from the chapter ‘The Evidence Bases in Religion, Science and Politics,’ and explores how a Wisdom or Religious tradition comes about. It follows on from The Scientific Tradition.

The Wisdom tradition

But what about a Wisdom tradition such as Buddhism? Here the authors [of The Embodied Mind] draw upon the philosophical tradition of Phenomenology, in particular the work of Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. The Greek word logos traditionally means ‘word, thought, principle, or speech’ and has been used among both philosophers and theologians, and the word phenomenon—which because it comes from the Greek phainomenon, from the verb phainesthai, meaning “to appear, become visible”—means ‘appearance’ and so the word Phenomenology can be glossed; ‘what you can say about the phenomena of experience / what appears to be in the world, (by implication) if you set aside speculative theories, for instance theories about whether you and the world exist, whether there are “real objects” out there.’ Martin Heidegger’s’ answer was ‘you appear in the world as if thrown here’ and the appropriate response to your existential situation was ‘care;’ you should look after yourselves and your world (Heidegger has a critique of technological excess that is very pertinent today).

Phenomenology ‘pushes us back onto our experience’, and the authors call this experience ‘first-person experience’ or ‘first-person evidence;’ because it is only accessible to a first person (to an ‘I;’ to oneself).

This is relevant today: Critical Race Theory and proponents of Woke assume that all white people are racist. Obviously, it is possible to tell whether someone is racist from their words and actions, but beyond that, such a realization can only come from self-knowledge and awareness: in other words, from a first-person perspective. The only person who can truly know for certain whether they are racist is the person themselves: as they are the sole person with access to their inner world. And what they do with that knowledge is their business: this is how conscience works.

In Buddhism, for true confession to take place, the practitioner must see their failing for themselves; any person hearing a confession is only witness to an inner process. Confession therefore is a ‘first-person to first-person’ matter, just as a preceptor witnesses a Buddhist ordinand’s effective going for refuge to the Three Jewels.

Varela [co-author of The Embodied Mind] went on the create a new field; Neurophenomenology, bringing together neuroscience—including the scientific study of brainwaves of meditating monks—with first-person reports of meditative experience. I explored these ideas in a Shabda[1] article entitled ‘Consciousness and the Embodied Mind: Phenomenology, Cognitive Therapy and the Satipatthana Sutta’ (2007).[2]

Yet Varela et al did not envision the scientific pyramid I talked of earlier, nor did they speculate about how a religious tradition is established through a wisdom community amassing first-person evidence, which I do below.

The Kalama Sutta

In the Kalama Sutta the Buddha clearly states how each person needs to judge for themselves—with one eye on wise opinion—which teachings they should accept, and which reject:

‘Kalamas, when you know of yourselves that these teachings are unskilful, blameable, faulted by wise people that, followed through, and practised, they lead on to harm and suffering, then give them up.

‘…But when you know of yourselves that these qualities are skilful, blameless, recommended by wise people, and that followed through and practised they lead to welfare and happiness, then practise them and stick to them.

‘…Then a follower of the sages, who is free from this sort of covetousness and ill-will, and is un-deluded, with clear comprehension and mindfulness, lives with his heart full of universal loving kindness (metta). He extends his kindness to each quarter in turn, and above and below, and in all directions, to all living beings as [to] himself. He lives with his heart filled with abundant, exalted, and limitless metta, free from hostility, unaffected by ill-will, extending to the whole world (…likewise with compassion, sympathetic joy and equanimity).’[3]

Confidence in Buddhism is established on three grounds: reason, intuition and experience. It is through examining for ourselves whether a teaching; a) makes sense, b) feels right and c) works in experience, that we make a ‘first-person judgement’ about the teaching. We also make a similar first-person judgement about who we consider to be wise and therefore whose recommendations we follow.

The Religious Tradition Pyramid

If I decide to go for refuge to the Three Jewels in the context of Triratna (as enacted in my private ordination) I make that choice as an individual, no one makes it for me. Before and after me, other individuals independently made the same choice, based on their own first-person experience. What is created is a spiritual community built around these choices, represented by a second (Wisdom) pyramid, but now based upon first-person evidence. Those in the community with greater clarity, commitment, and ethical exemplification (‘the wise’) will tend to ‘rise up’ the pyramid in a natural hierarchy.

Notice how Wisdom replaces scientific objectivity when we move from third-person evidence to first-person evidence, although there comes a different kind of objectivity with Wisdom; we might call this ‘Objective Subjectivity.’

Not all religions though are true wisdom traditions; as I indicated earlier, there is a spectrum from true wisdom tradition through to cult. I suggest that the test of any religion being—or the degree to which it is—a true wisdom tradition is that through its views, narratives and practices the world becomes a happier wiser place. A cult—bringing as it does suffering into the world, in comparison could more accurately be described as an ‘ignorance tradition.’

Any religious tradition, a school or sect within a tradition, or secular system acting like a religion will be sited somewhere on the wisdom-ignorance spectrum. As my old physics teacher Jock Marsden used to say (He was Scottish): “You pays your money and you takes your choice.” That system that we place faith in has consequences for ourselves and others; and the world rises and falls by whatever decision we make.

The Threefold Way as corrective

The Buddhist wisdom pyramid is constructed ‘from’ Ethics, Meditation and Wisdom, and is based on first-person experience. We normally think of these three elements as being in a hierarchy where meditation naturally builds upon ethics; and wisdom naturally builds upon meditation, but we can choose to view the triad in a quite different manner, in which each element acts as a corrective to the one below, namely:

Meditation as corrective to ethics

We practise ethics in everyday life and reach a certain level of ethical sensitivity that we feel quite pleased about, but when we meditate more thoroughly, we notice deeper aspects of our psyche to which our ethics has not penetrated: in this way our meditation is a corrective to our ethics.

Wisdom as corrective to meditation

The process is similar with Meditation and Wisdom. Maybe there is a tendency among some Buddhists to believe that practising meditation will naturally (Sanskrit: dharmata) and inevitably lead to wisdom if one practises enough, but a good number of the sixty-two wrong views outlined in the Brahmajala Sutta concern mistaken views about meditative attainments; for instance, confusing the fourth dhyana with Awakening.

Likely, Zen Buddhism arose in reaction to scholasticism; its’ ‘mantra’—to quote Bodhidharma, Zen’s first patriarch—could be said to be:

‘No dependence on words and letters;

Directly pointing to the mind.

Seeing into one’s true nature

And attaining Buddhahood’

Temperamentally, a good number of Buddhists are averse to—and indeed suspicious of—intellectual formulation, choosing instead Zen’s aesthetic approach which focuses on a simple lifestyle and harmony with the nature world, as expressed in the wabi-sabi aesthetic:

‘These two amorphous concepts are used to express a sense of rusticity, melancholy, loneliness, naturalness, and age, so that a misshapen, worn peasant’s jar is considered more beautiful than a pristine, carefully crafted dish. While the latter pleases the senses, the former stimulates the mind and emotions to contemplate the essence of reality.’[4]

Zen masters challenge each other until, through mutual acknowledgement of whose realization is the greater, one succeeds the other, all of which, I assert, is based upon first-person experience, the whole Zen edifice depends upon having masters at the top of the pyramid who have real wisdom: and thus who are able to correct wrong views about meditation and ethics. This situation was sorely lacking in Second World War Japan when accredited Zen masters actively supported the war effort.[5]

And this is the case with any group who rely on personal experience as adjudicator; today there are groups within the Triratna Buddhist Order who especially focus on insight meditation; and as any group with a common interest can operate as a kind of echo chamber, at some point there needs to be a reality check not only on the effects of the meditation they are practicing, but on the kind of people they are becoming. In this way, there is no getting away from the fact that the health of any wisdom tradition depends on having people with real wisdom at the apex of the pyramid.

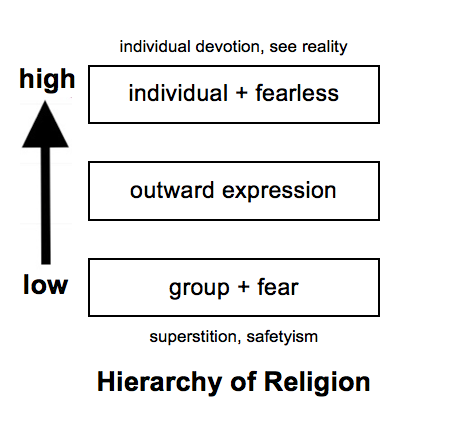

Certainly, akin to the hierarchy observed in science, religion also exhibits a hierarchical structure. Not all religious beliefs uphold the same level of wisdom; rather, there exists a spectrum ranging from profound individual religious insight and dedication to group-oriented, fear-based cults. The measure of evaluation for any religious practice rests in its ability to offer salvation-oriented solutions to a broad array of individuals. In contrast, behaviours rooted in cult-like practices and superstition may offer temporary solace but cannot be classified as objective religious traditions in alignment with truth.

The chapter goes on to explore The Political Tradition.

[1] The in-house journal of the Triratna Buddhist Order.

[2] ‘Consciousness and The Embodied Mind: Phenomenology, Cognitive Therapy and the Satipatthana Sutta.’ (2007) Mahabodhi.

https://mahabodhi.org.uk/MB/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ConsciousnessEmbodiedMind.pdf

[3] AN I 189–190. Ratnaprabha 1988, with adaptations.

[4] Department of Asian Art. ‘Zen Buddhism.’ In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/zen/hd_zen.htm (October 2002)

Original quote: ‘Zen Buddhism’s emphasis on simplicity and the importance of the natural world generated a distinctive aesthetic, which is expressed by the terms wabi and sabi. These two amorphous concepts are used to express a sense of rusticity, melancholy, loneliness, naturalness, and age, so that a misshapen, worn peasant’s jar is considered more beautiful than a pristine, carefully crafted dish. While the latter pleases the senses, the former stimulates the mind and emotions to contemplate the essence of reality. This artistic sensibility has had an enormous impact on Japanese culture up to modern times.’

[5] See Brian Victoria’s Zen at War.

Users Today : 113

Users Today : 113 Users Yesterday : 23

Users Yesterday : 23 This Month : 571

This Month : 571 Total Users : 13998

Total Users : 13998