Below is an excerpt from my forthcoming book…

© Mahabodhi Burton

7 minute read

This excerpt is from the chapter ‘Transhumanism and alienation’ and it explores the cyborg nature of social media in the human-machine interface: with input from Elon Musk being interviewed by Joe Rogan.

Silicon life viewed from Space: a thought experiment

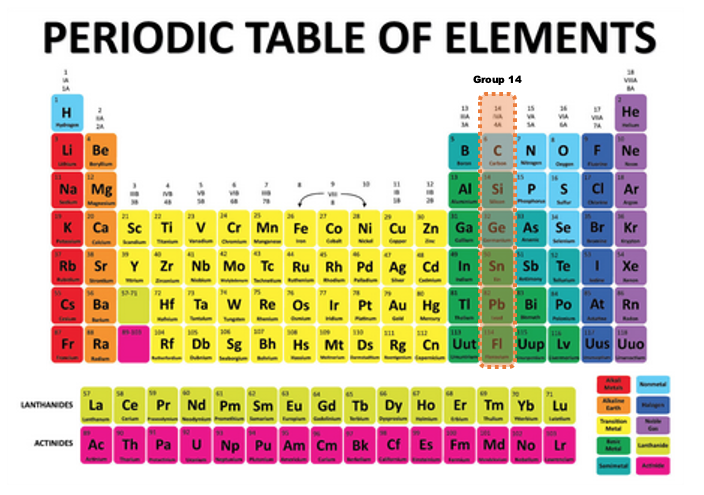

Years ago, I remember reflecting on the Periodic Table of the elements and on the fact that all the elements in a column have the same number of electrons in their outer shells: and therefore, similar properties. Carbon (symbol C)—the element on which organic life is based—has four electrons in its outer shell, as does Silicon (symbol Si.) Along with Germanium (Ge,) Tin (Sn) and Lead (Pb,) they make up Group 14 of the table. I therefore came to reflect on whether there could ever be such a thing as a silicon-based life form, and if so, what it be like.

Life only exists—and thus, continues to be life—when the conditions necessary to maintain its existence are present. Human life, thus, is supported by a network of conditions, which includes other animals, plants, water, air, soil, and so on. A life-form existing independently of its supportive conditions is just not possible.

Organic life is defined as possessing certain qualities:[1] such as the ability to reproduce and homeostasis.[2] But let’s conduct a thought experiment: suppose an alien were to look down from Space, down at the Earth, over the past thirty years. They would see the number of personal computers grow to 1.4 billion, and smart phone users, as share of the global population, to 78%; all ‘attached’ to their users: human beings.

Not knowing what they were looking at, the alien might assume they were watching a silicon-based life-form reproducing and evolving in homeostatic symbiosis with its supportive host (the human). They might even wonder whether humans were not being put into service by those life-forms; in the same way that humans farm cattle: the humans feed the computers with information, and in return they receive mental stimulation and organisation. We are not talking about Skynet here, but something more mundane.

If computers are truly ‘alive’—in their own silicon-based sense, then the question of ethics arises. Are their activities truly benefitting humans; or have humans to some extent become their slaves.

Social media as a cybernetic collective

In 2018, there was an interesting interview with Elon Musk by Joe Rogan,[3] in which Musk points to the ‘cyborg’ nature of social media:

‘A company is essentially a cybernetic collective: of people and machines. And then, there is different levels of complexity in the way these companies are formed. And there is a sort of collective AI in the Google search, where we are all plugged in as nodes on the network, like leaves on a big tree. We are all feeding this network, with our questions and answers. We are all collectively programming the AI. And Google, plus all the humans that connect to it, are one giant cybernetic collective. This is also true of Facebook; and Twitter; and Instagram; and all these social networks.’

Such a cybernetic collective would correspond to a hybrid silicon-carbon-based life form:

Rogan: ‘Humans and electronics, all interfacing, and constantly connected! … (Peoples’ desires for the next thing) is fuelling technology and innovation. It seems like it’s built into us—what we like and what we want—that we are fuelling this thing, that’s constantly around us all the time. It doesn’t seem possible that people are going to pump the brakes. … Where we are constantly expecting the newest cellphone; the latest Tesla update; the newest Macbook Pro: everything has to be newer and better: and that’s going to lead to some incredible point. And it seems like it’s built into us: it almost seems like it’s an instinct. That we are working towards this: that we like it. Our job: just like the ants build the anthill; our job is to somehow or other fuel this.’

Musk: ‘It feels like we are the biological boot loader for AI effectively; we are building it. And then, we are building progressively greater intelligence; and the percentage of intelligence that is not human is increasing. And eventually, we will represent a very small percentage of intelligence. But the AI isn’t formed—strangely—by the human limbic system, it is—in large part—our id writ large.’

Rogan: ‘How so?’

Musk: ‘Well you mentioned all those things, the primal drives. There’s all the things that we like, and hate; and fear: they are all there on the Internet. They are a projection of our limbic system.’

Rogan laughs in amazement, but also slightly nervously: and he agrees: ‘No, it makes sense. Thinking of corporations, and just thinking of human beings communicating online through social media networks as some sort of organism: it’s a cyborg. It’s a combination of electronics and biology.’

Musk: ‘The success of these online systems is a function of how much limbic resonance they are able to achieve with people: the more limbic resonance; the more engagement.’

Rogan: ‘Whereas one of the reasons why Instagram is more enticing than Twitter … is more limbic resonance … more images; more video: it’s tweaking your system more. Do you wonder what the next step is? A lot of people didn’t see Twitter coming.’

Regulating AI

Musk says things getting more and more connected but are at this point constrained by bandwidth: our input-output is slow: particularly our output. He says he tried to get people to slow down AI; to regulate AI: nobody listened. He says the process of regulation is always slow.

‘Normally the way that regulations work is very slow. Usually there will be some new technology; it will cause damage or death; there will be an outcry; there will be an investigation, years will pass; there will be some sort of insight committee; there will be rule-making; then there will be oversight, eventually; then regulations; this all takes many years.

‘This is the normal course of things: if you look at, say, automotive regulations; how long did it take for seat-belts to be required; the auto industry (successfully) fought seat belts for more than a decade, even though the numbers were extremely obvious. … Eventually, after many, many people died, regulators insisted on seat-belts. This time-frame is not relevant to AI; you can’t take ten years, from the point at which it’s dangerous, it’s too late!’

Musk says we’re not necessarily in a Doomsday countdown: it’s more that it is out-of-control. He says, ‘People quote the singularity, and that’s probably a good way of thinking about it … like a black hole, it is hard to predict what happens past the event-horizon.’ Once it is implemented, it is difficult to predict what will happen: AI will be able to improve itself unrecognizably; according to Musk: ‘It could be terrible, and it could be great: it’s not clear. … one thing is for sure: we will not control it.’

Rogan: ‘Do you think that it is likely that we will merge, somehow or another, with this sort of technology, and that it will augment what we are now, or do you think it will replace us.’

Musk: ‘The merge scenario with AI is the one that seems, like probably the best (for us). If you can’t beat it, join it. … From a long-term existential standpoint, that’s like the purpose of neural link: to create a high bandwidth interface to the brain, such that we can be symbiotic with AI. Because we have a bandwidth problem: we just can’t communicate with our fingers: it’s too slow.’

Musk goes on to describe the current progress with developing neuralink, an implantable brain-machine interface.[4]

The Three Laws of Robotics

The science-fiction writer Asimov drew up Three Laws of Robotics and later added a fourth: the Zeroth Law, which obviously comes before the First Law.[5] These Laws have affected thought on ethics of artificial intelligence.

- Zeroth Law—A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.

- First Law—A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- Second Law—A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- Third Law—A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

For Asimov, AI needs to be Buddha-like: unmorality is not an option.

We are local rather than global

In the final chapter of War of the Worlds, ‘The Case for Essentialism’,[6] Mark Slouka offers some reflections:

‘Let me start my conclusion with a familiar bit of free-market heresy: what’s good for business is not necessarily good for culture. The digital revolution is probably good business; culturally, in many ways, it’s bad news.

‘It’s bad news—another larger heresy—at least in part because it’s a product of the new globalism; and globalism, while both admirable as a metaphor for tolerance and effective as a marketing strategy, is an abstraction at once too vast and too airy for most people to live by. Human beings, no less than other species, are more local than global. We are shaped, each of us, by the particulars of the cultures we inhabit. Identity, in other words, is in the details, and though the individual may colour these details in his or her own way, the physical aspect of life in the real world is an invaluable source of self-knowledge.’[7]

Brent Staples,[8] writing in 1994, says the push for complete ‘in-touchedness’ offers a glimpse of the end of solitude, of a time … when portable phones, pagers and data transmission devices of every sort keep us terminally in touch, permanently patched into the grid. … Solitude will become ‘down time’ to be filled in with gadgets. We are at that point.

The chapter goes on to explore the remedy for alienation in facing emotion and developing an accurate view of oneself and others through cultivating universal loving kindness.

[1] All living organisms; 1) respond to their environment, 2) grow and change, 3) reproduce and have offspring, 4) have complex chemistry, 5) maintain homeostasis, 6) are built of structures called cells, 7) pass their traits onto their offspring. From Characteristics of Life. CK-12 Foundation.

[2] Homeostasis is any self-regulating process by which an organism tends to maintain stability while adjusting to conditions that are best for its survival. If homeostasis is successful, life continues; if it’s unsuccessful, it results in a disaster or death of the organism. ‘Homeostasis’ Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/Science/homeostasis

[3] ‘Joe Rogan Experience #1169 – Elon Musk.’ PowerfulJRE. YouTube. 7 Sept 2018. From 14:57 mins.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ycPr5-27vSI&t=1246s

[4] Neuralink Corporation is a neurotechnology company that develops implantable brain–machine interfaces (BMIs). See Neuralink. Wikipedia. Accessed 24 October 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuralink

[5] ‘Three Laws of Robotics.’ Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Laws_of_Robotics

[6] Mark Slouka (1995) War of the Worlds: Cyberspace and the High Tech Assault on Reality. Abacus. p119-120.

[7] Slouka continues; ‘It’s a kind of self-knowledge directly threatened by the abstractions of the digital revolution, whose backers, like former Citicorp chairman Walter B. Wriston and current U.S. Secretary of Labor Robert Reich, laud the I-Way’s ability to “empower” individuals, without bothering to point out that empowerment has more than one definition. What they offer us, generally speaking, is a vision of cyberspace as free-market utopia; what they tend to leave out is any suggestion that abstracting our lives may be bad for us, that the virtual community–to use the title of Howards Rheingold’s book–is an oxymoron, and that the new global citizen may actually turn out to be a new kind of exile–an electronic wanderer wired to the world but separated from much that matters in human life.’ See Walter B. Wriston. (1992) The Twilight of Sovereignty: How the Information Revolution is Transforming Our World. New York: Scribner’s.; Robert Reich. (1991) The Work of Nations: Preparing Ourselves for 21st Century Capitalism. Knopf. Howard Rheingold. (1993) The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. New York: Harper Perennial.

[8] Brent Staples. ‘Life in the Information Age: When Burma-Shave Meets Cyberspace.’ Editorial Notebook, New York Times. 7 July 1994.

Users Today : 88

Users Today : 88 Users Yesterday : 23

Users Yesterday : 23 This Month : 546

This Month : 546 Total Users : 13973

Total Users : 13973