Below is an excerpt from my forthcoming book…

© Mahabodhi Burton

7 minute read

This excerpt is from Chapter 10 and follows on from The Fourth Dhyana.

Vipassana meditation

In general, vipassana meditation takes place on a firm foundation of samatha meditation.

‘Vipasyana, the insight method of meditation, reveals our self and our world as they are beyond our assumptions and self-referencing emotions. It is direct experience, not abstract understanding, and contrasts with samatha methods such as mindfulness of breathing that prepare the mind for vipasyana by cultivating profound concentration and strong, positive emotional integration. Vipasyana is generally preceded by samatha practice, because if concentration is wavering, the mind will be unable to rest in the special object of vipasyana meditation. And when insight comes, a stock of calm, strength and happiness is needed in order to absorb its revelatory, visionary impact.’[1]

Hence:

In dependence on concentration there arises knowledge and vision of things as they really are (yathabhutajnanadarshana)

Knowledge and vision of things as they really are

On the basis of the fourth dhyana, the monk is now ready to reflect on the nature of reality.

‘Then with the mind composed, quite purified, quite clarified, without blemish, without defilement, grown pliant and workable, fixed, immovable, he directs his mind to …’[2]

To some extent we have already been reflecting on the way that things are; in the sense of understanding that the bottom line for all sentient beings is that they desire happiness and do not want to suffer, and that the way that happiness is brought about is through wanting it for all beings—in the cultivation of metta towards them—and in bringing mindfulness to the situation to see precisely what needs to happen in order to bring it about. And we saw that we needed to understand how the mechanism of Conditionality pervaded all aspects of that process, so that a constructive approach to overcoming suffering could be followed, as represented by the dhyanas.

With insight—or wisdom—practice, we now come to explore the more destructive aspect of Conditionality; the fact that whatever we possess; create; love; are attached to, to the extent that it exists in Samsara; Unenlightened Conditioned Existence, will eventually fall apart. This truth is expressed in the three laksanas (Sanskrit: trilakshana; Pali: tilakkhana), or marks of Conditioned Existence; that all such phenomena are impermanent (anicca), insubstantial (anatta) and thus unsatisfactory (dukkha). To understand how the former fits in with the latter, it will be useful to consider a metaphor.

The Anatta Doctrine and the potential hill[3]

The Buddha was born 2,500 years ago in India, into a culture which held views very similar to those held by Hindus today; before the Universe existed, it was held that there was just pure being, called Sat. That ‘being’ then decided to bring the Universe into being, and one by one the various phenomena of the Universe ‘fell out’; the elements, human beings and so on. The central idea in Hinduism is that behind the phenomenon of changing personality is something fixed, a permanent essence or self, called in Sanskrit atman, in Pali atta. Likewise, behind the phenomenon of changing Universe it imagined a permanent entity called Brahman. And the point of Hindu practice is to try to get back to realizing this pure being in meditation, as represented by the atman, and seek to merge it with Brahman.

Buddhism on the other hand has the doctrine of non-self; when the Buddha-to-be looked into his experience he could find no fixed self, only a changing flux of conditions. Among Buddhists there seems to be quite a bit of confusion—and I would propose laziness—about the true meaning of the term anatta: Does the anatta doctrine mean that there is no self at all—and therefore no agency, a conclusion which some jump to? Or is there a self—and hence agent, but is that self conditioned and therefore impermanent? Dhivan comments:

‘While the self, considered as apart from ordinary experience is ultimately non-existent, the everyday self appears to exist. What is denied in Candrakirti’s analysis is just that this ordinary sense of self exists in the manner in which it appears to exist, which is to say, as existing apart from what it depends on.’[4] (My emphasis)

The problem is not so much with the self per se but with its ego identification and its appropriation of things.

‘What appears is my experiential self that appears to exist independently, but how this self appears is dependent on ego identification and the appropriation of the constituents.’[5] (My emphasis)

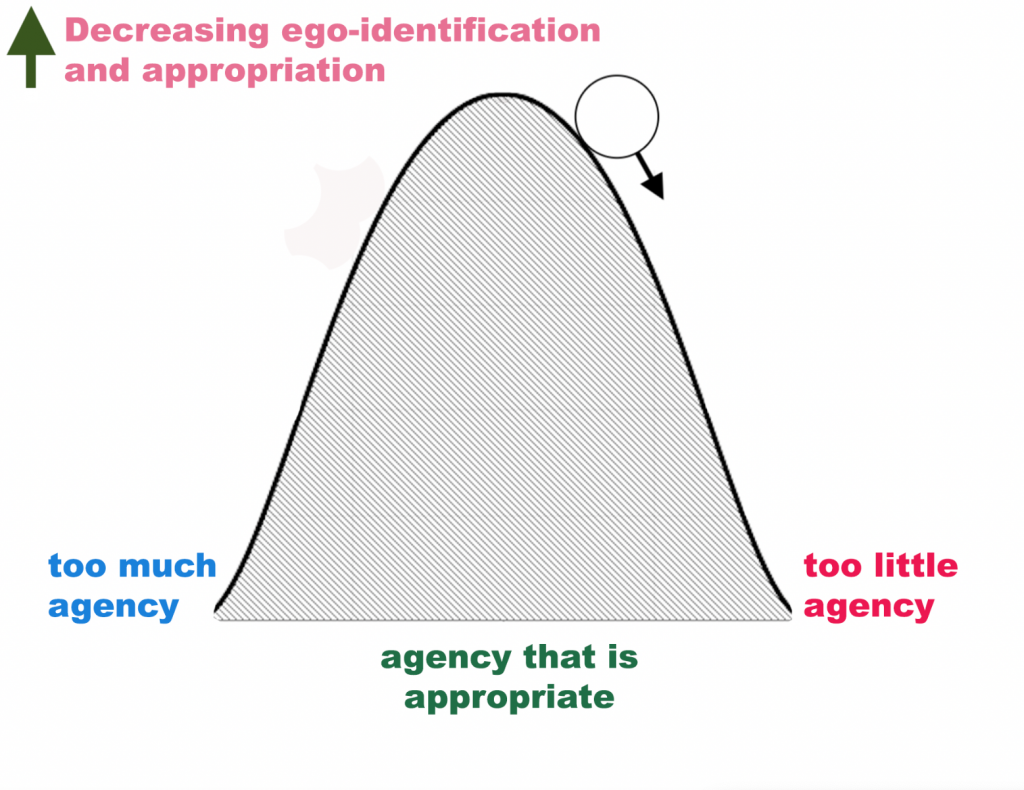

The situation can be best explained with a diagram; think of a graph with two axes: along the bottom axis we have increasing agency, up the left axis we have decreasing ego identification (“This is me”) and appropriation (“This is mine”).

Buddhism is all about overcoming suffering, for ourselves and others. To achieve this we aim to cultivate universal loving kindness towards all living beings—which gives us the motivation to want to help them (without which no means exist)—and mindfulness—which helps us bring awareness to the details of their actual situations and thus to knowledge of what will help them. With these two great pillars of Buddhism as our basis we will want to and we will know how to practise ethics.

To practise ethics wisely we need to have an accurate view of our agency. The best way to understand the anatta doctrine—incorporating Candrakirti’s analysis—is to see ourselves as part agent—namely, that there are some conditions in life that we are responsible for; our mental states and actions of body, speech and mind—and part non-agent—we are not responsible for the actions of others for instance.

To think that there is no self is to assume too little agency, and thus deny responsibility for our mental states and actions. But if we take the opposing extreme view and assume that we are completely responsible for everything—even things we have not done, this is to assume too much agency: a position represented by the atman, a source of irrational theistic guilt and the philosophical basis for the Hindu caste system, where a person’s spiritual capability is seen as inalterable, and fixed at birth.

In the diagram, ‘no agency / no self’ and ‘complete agency / fixed self (atman)’ correlate with the extreme views of Annihilationism—the belief that everything ceases at death—and Eternalism—the belief that a permanent essence or soul continues on after death. But what about ‘part agency / non-self (anatta)?’

A potential well is a term known in physics and it can be represented by a U-shaped structure like a bowl. When we place a ball in a bowl it will move towards the centre and then oscillate back and forth until it comes to rest in the bottom of the bowl. If we invert the bowl, we end up with what we might call a potential hill; here, wherever we place the ball, it will tend to want to roll down the hill, to one side or the other.

The Middle Way that the Buddha proposed between the extremes of Annihilationism and Eternalism is represented by the potential hill. Rather than it being some kind of ‘mean’ between Annihilationism and Eternalism, the Middle Way is more like a ‘higher third’ above and beyond them.

The hill analogy suggests that a Middle Way is inherently difficult to establish and maintain. Firstly, we need to establish (and keep in mind) the fact that Buddhism is exclusively concerned with overcoming suffering, and not just our own suffering; if we take the Buddha’s example seriously, the sufferings of all sentient beings, as outlined in the Mahayana Bodhisattva Ideal.

If this is the task we choose to take on—and it is our choice, we are talking about an enormous hill to climb, even if we are only thinking of our own suffering, never mind that of other beings. The Bodhisattva Ideal is not so much a literal goal, it more expresses a certain attitude; that we are as interested in creating the conditions for overcoming the suffering in others as we are in creating the conditions for overcoming it ourselves. Of course, Buddhism sees the two as related; that spiritual progress-and therefore personal happiness-involves being less concerned with what is ‘me and mine’ and instead concerned with the general welfare. Luckily, (so long as we don’t take it literally) the task is within our power, but only if we are systematic in building up and maintaining our awareness and clear comprehension (sati and sampajanna) one moment at a time, in fact everything implied in cultivating the four foundations of mindfulness.

As ‘part agent’ we have to take responsibility where due, so that we don’t slide down the slope into inaccountability (i.e., no self). There is an aspect of ‘self power’ to the path.

At the same time, we need to know when to stop taking responsibility, so that we do not over-reach in that way, and look for support in the conditions outside of ourselves (friends, mentors, higher spiritual power.) Otherwise, in our isolation, we will take everything problematic unto ourselves and be weighed down by the burdens of the world (i.e., fixed self). There is an aspect of ‘other power’ to the path.

In every aspect of the spiritual life there are tensions we need to overcome if we are to remain in the ‘middle.’

One major tension is that between ‘perspiration’ and ‘inspiration.’ In other words, ‘making effort’ (with ethics) versus ‘withdrawing’ (to become resourced again), a pattern expressed in the ideal Buddhist lifestyle, which balances compassionate activity with regular retreat attendance.

A similar major tension exists between self and other. Do we make sure we are in a good state and well-resourced before we give our attention to others; the analogy is often given that when we are in an emergency, we need to put our life jacket on first, before we help others with theirs?

And in terms of creativity and dissolution there is also a major tension. Due to the law of impermanence, whatever benefits our spiritual efforts might bring to the world, those benefits will eventually be subject to decay and dissolution. If we aren’t to become dispirited, we need to be accepting of this reality. Practising the Middle Way (as a Bodhisattva) therefore involves the willingness to put in a massive effort to foster the conditions for happiness for living beings, while at the same time not expecting the fruits of those actions to continue. This is what it means to possess a deep realization of the law of Conditionality; accepting impermanence is not enough on its own, we must accept it in the context of full commitment to altruistic activity in relation to living beings.

Spiritual life then is like the potential hill; we must keep making the effort to bring opposites together; activity and retreat; self and other; creativity and its dissolution. We have to bring the skilful into being on the level of our psychophysical energies; through ensuring that our body—having had enough exercise and sleep—is vital yet relaxed. Likewise, that our mind is alert, but also malleable and receptive.

It is easy to drift into unawareness and go for something mind-numbing like watching daytime television; this is to ‘fall down’ the hill on the ‘no agency’ side. It is also easy to drift to its opposite, by putting ourselves ‘under the cosh’ and adopting a punitive workaholism (assuming overbearing agency.) Neither position is mindful of the true situation. Or we may oscillate between the two poles; exerting ourselves unreasonably but then falling into complete exhaustion; we need a consistent and disciplined Middle Way guided by mindfulness in most things!

Not only that, whatever we do create that is skilful will inevitably decay, change, fall apart. One of the greatest challenges in life is to keep upright, positive, adaptable in the face of that, and not get despondent. In fact, I think that this is what insight really consists in; not collapsing or losing our faith when this happens.

And when we see the effects of our actions dissolve, to not drift into a mindset where we think ‘What’s the point?’

Of course, it is hard work to try to overcome narrow ego identification, self-obsession, and our tendency to appropriate material things, status and so on. In supportive conditions we might rise above these latent tendencies for a while, but to do so requires effort. Once we tire or stop paying attention we will tend to sink back down into a more self-oriented, unaware state and this is represented by the hill in the diagram.

The chapter goes on to explore Insight and Ethics.

[1] Kamalashila. (2012) ‘Buddhist Meditation: Tranquillity, Imagination and Insight.’ Windhorse. Chapter 8.

[2] Dantabhumi Sutta. MN125 Access to Insight.

https://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/mn/mn.125.horn.html

[3] I have summarized this idea in a short video on ‘Non-Self and Agency.’ See the ‘Featured’ section of my YouTube channel:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UClq5Zl9iUVPunBbbYVWucSw

[4] Dhivan Thomas Jones. Three Ways of Denying the Self. Western Buddhist Review Volume 7 p41.

[5] The constituents are the five skandhas; the five elements into which the Buddha analyses the personality; namely form, feeling, volition, apperception and consciousness.

Users Today : 104

Users Today : 104 Users Yesterday : 23

Users Yesterday : 23 This Month : 562

This Month : 562 Total Users : 13989

Total Users : 13989